I was five years old when my family immigrated to the greater Boston area from Iran. The Portuguese kid next door in our shady apartment complex could not pronounce my name so he called me “Charlio,” the origin of my name. I was light skinned and looked like Russell from Pixar’s “Up.”

A GROWING SEPARATION

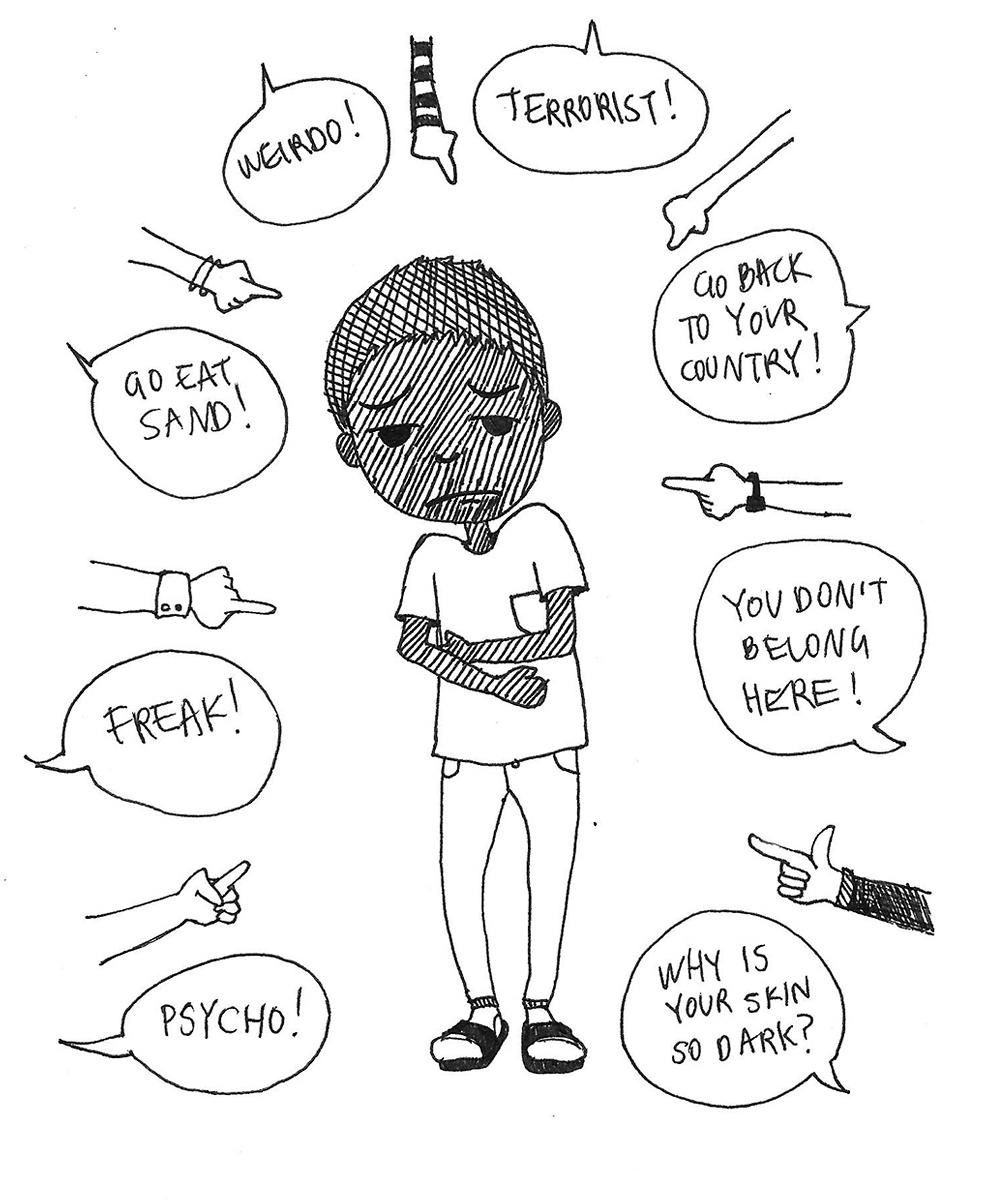

With my broken English and embarrassing Iranian lunches, kids made fun of me and treated me differently. I envied the coveted brown lunch bag the “normal” kids brought. I even tried to find acceptance on the playground by crushing everyone else in Pokemon games.

I vividly remember the day our teacher tearfully explained the 9/11 attacks, and that our families would come pick us up since we were just a few hours drive from the burning Twin Towers. The next day JFK’s brother, Ted Kennedy, swore my mom and I in as citizens. What timing, right?

I remember waiting to get picked up from school a week after the discovery of Al-Qaeda’s responsibility for the attacks. A friend turned to me and gave me this look, “Wait…where are you from again? Iran? Oh man…you’re one of the terrorists!” I was an eight-year-old chubby Japanese-looking “terrorist” and I was confused. Had I offended my friend?

As I got older, I grew more aware of my foreignness as my skin darkened. Friends called me a terrorist and a sand n****r, they mimicked suicide car bombings when I was around. Thankfully, all of this seemed to cease when I transferred to Biola.

Last year, I had friends over for a barbecue and my mentor said, “That’s so Middle Eastern of you.” Had I served kabobs and rice then maybe it would have been true, but I served barbecue. This person based a stereotype off my appearance, not my action or character.

MISSING THE POINT

The same semester as the barbecue incident, I began to notice the new shift towards emphasizing diversity on campus and I became eager for the Student Congress on Racial Reconciliation conference. But my friends left the SCORR conference feeling ashamed and guilty for being white. The conference seemed to focus more on detailing how hurtful white people have been and less on encouraging diversity.

Accordingly, I walked away from the conference feeling even more frustrated. SCORR emphasized the past suffering of various races, the exploitation of the socially marginalized and a robust message that ironically sounded like stereotyping white men as bigoted oppressors. I hardly remembered hearing about Jesus; in the midst of reconciling racial tensions on our campus, we had forgotten about our savior.

My view of SCORR is only one perspective, but it lead me to believe that we cannot point the finger back at one another and further divide the body of Christ. Christ calls us to love others with the same love we have for God. We must strive to respect and know our fellow man without hasty judgments, stereotypes and prejudices, lest we forget the unifying and redeeming work of Christ.

Our fear of what appears different often leads us to deeply wound each other and becomes intensified in a culture that hides behind the veil of anonymity created by technology. Have we forgotten grace and instead begun limiting our views of each other because we see things we do not like? If so, we have forgotten to love each other.

We are the Church, a body of believers that look and speak differently, united by the redeeming work of Christ. If we as a university continue to single each other out — even in an effort to appreciate our differences, we lose the unifying power of Jesus.