Politics: The Durbin Amendment

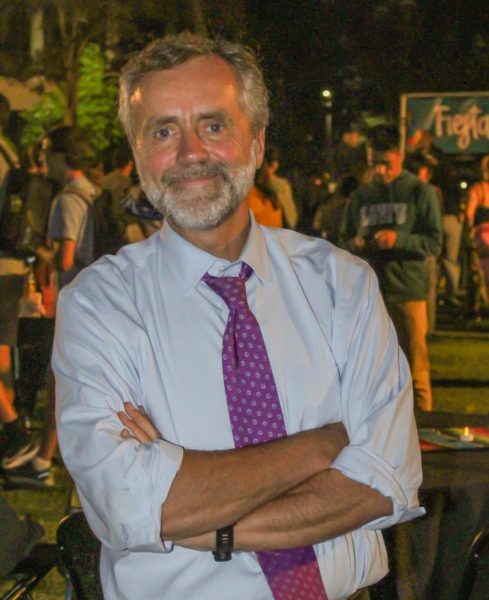

Albert Cheng discusses the Durbin Amendment and its affect on banks and customers.

October 13, 2011

How would you like it if you were pilfered five bucks each month beginning next year? If you don’t know how it feels, you may get a taste if you are a Bank of America customer and use your debit card. If you bank elsewhere, you had better keep up with any new, emerging fees and restrictions on debit card use.

Now, let’s not be like many Occupy Wall Street individuals and impulsively lash out at those supposedly greedy banks for scalping their customers of every last penny. It is not entirely their fault.

Senator Richard Durbin also deserves some blame. In May of 2010, he introduced an amendment to the Frank-Dodd Act which President Obama signed into law two months later. Banks are now only rationally responding to this legislation.

What does the Durbin Amendment do?

When consumers like you and me use our debit cards to make a purchase from a merchant, the merchant must pay a fee to our bank. After all, there is a cost to process and wire the transaction. This fee is called an interchange fee, and the Durbin Amendment limits it to 12 cents.

Contrast this with life before the amendment, where the interchange fee was typically 1.14 percent of the purchase price. Suppose you go to Best Buy and use your debit card to purchase a new digital camera for $200 so that you can take pictures of all your Biola memories.

Without the Durbin Amendment, banks would charge Best Buy 1.14 percent of $200, or $2.28. With the Durbin Amendment, the banks can only charge Best Buy 12 cents. It may seem trivial that the banks only lose $2.16 in this example, but imagine the billions of dollars that banks lose when these transactions are repeated on a much larger scale.

Banks must consequently find ways to recoup the lost revenue to remain in operation. And that is by no means a greedy move. It is self-interested, but hardly selfish; there is a difference between the two with only the latter being immoral.

Policymakers, then, should certainly neither be surprised at the banks’ actions nor point their own guilty fingers at them.

Government policies are not as inconsequential as you think

Whether the motivation behind policymakers is to be genuinely benevolent or to indulge their hubris by garnering political popularity, laws written in legislatures throughout the nation always have far-reaching, unintended consequences — some more noticeable and harmful than others.

Every Bank of America customer, for example, will notice a new $5 fee, but most people may not realize the smaller community banks that may struggle to keep their doors open because of the Durbin Amendment, as Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernankehas admitted. Nor may they comprehend the ways that any new fees and restrictions can become yet another burden on families who currently have financial struggles.

Time will only reveal other unforeseen effects. The cost of the Durbin Amendment is not a simple five bucks each month, and the stakes might just get higher before we know it when it comes to additional issues of immediate relevance such as college financial aid and the U.S debt. Such prospects demand all of us to be watchful and to incline our ears to hear what the Spirit of the Lord is saying regarding developments in the policy arena.