Within the Green Art Gallery during March, “STATIONS: RESURGAM” by art professor Dan Callis explored themes of grief, lament, and meaning-making through a variety of multimedia pieces.

STATIONS: RESURGAM

The exhibition featured four different collections of artwork, including one group of fifteen different grief stations inspired by the Christian liturgical tradition of the Stations of the Cross. Another collection, titled “Hail Mary,” included four large oil canvas paintings. Three sculptures titled “Saints and Clowns” from a previous exhibition were also present, along with a multimedia installation with audio and visual components.

For the past three years, Callis’ exhibition has addressed nets of grief and lament over personal, social and global events that took place during the pandemic. Callis devoted the exhibition to his late son, Jeremy David Callis, who passed away from a ten-year opioid addiction in 2020. Callis noted the exhibition stems from not only his grief with the loss of his son, but also from recent communal grieving with the many losses the nation has faced.

“It became a whole other level of personal grief nested inside this larger [pandemic], and so there’s a body of work just about that. There are a number of works that are about the larger [pandemic],” Callis said. “But it’s also about hope and meaning-making. There was much joy [amid] all the disruption and we found new ways of being.”

GRIEF NETS

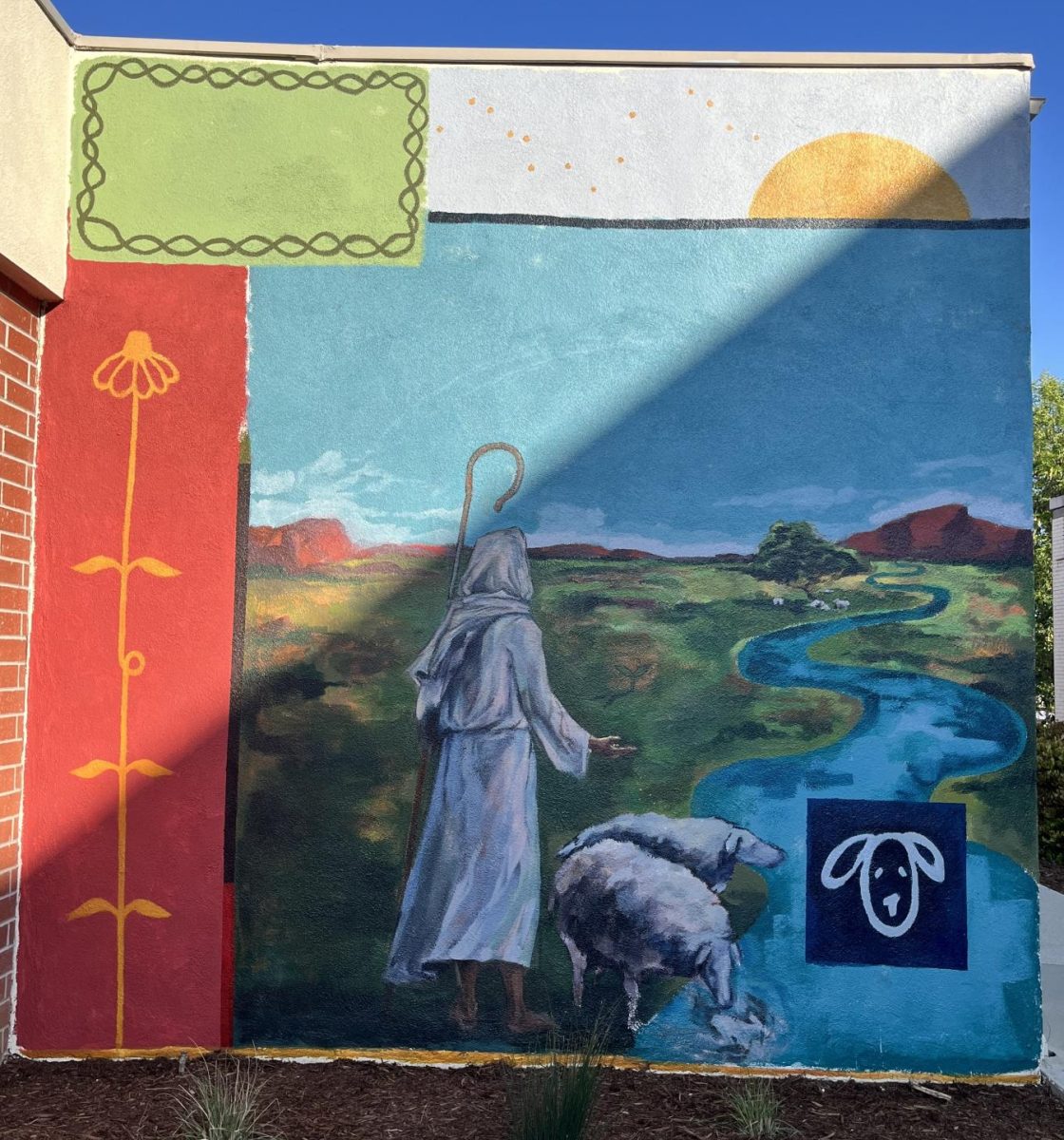

After entering the space, 15 different grief stations guide spectators through the Stations of the Cross, a depiction of the processional route Jesus walked to Mount Calvary, where he was crucified. The Christian practice is largely popular in Roman Catholic, Anglican and Lutheran denominations during the Lenten season.

According to the information provided in a QR code at the beginning of the exhibit, “the objective of the stations is to imprint upon the Christian a spiritual pilgrimage through contemplation of the Passion of Christ.”

Each station consists of a black and white framed work “consisting of a combination of mono-printing, block printing, hand and machine stitching, oil painting and mixed-media processes,” as stated in the QR code text. Alongside the framed works are ceramic bowls on top of a pile of ash that are meant to be a vessel representative of “emptiness and holds promise.”

Each framed work consists of a prevailing grid or net imagery that represents people’s ever changing lives. The distorted grid imagery is more prevalent in some areas of the canvas than others and contains both hand and machine stitching as parts of the net are repaired or changed. Within the grid-like patterns, viewers will notice that some parts of the net may be more prevalent than others. Callis explained that, like the portions of the net that stand out more, God’s presence was stronger in some instances than others during times of dealing with grief.

“I started working with imagery of the nets that appear to be breaking apart. And at the same time … I was aware that I was being held by friends and family members and my church community,” said Callis. “I was aware of the different nets being layered but I was very aware of God’s grace and mercy. At times, I couldn’t see it so you get bits and pieces of heavier net coming from outside.”

Callus also said that he had renamed each of the stations to allow for more people to relate their own personal grief to the artwork that was on display.

“I don’t use traditional Christian titles for the station because I wanted the titles to be able to hold everyone’s grief,” Callis said. “I wasn’t pointing to Christ’s conviction and crucifixion but to Christ as someone who walked [the path] before and for me at the time, it was a story of a father who lost his son.”

HAIL MARY

Scattered throughout the different grief stations are four larger pieces that are part of the “Hail Mary” collection. Initially, the project was created before the pandemic in collaboration with two Moroccan weavers, Aliza Chekhikem and Asmar Yayse. However, due to the constraints that Callis was placed in during quarantine, he decided to use the canvases for a separate project.

In contrast to the dark black and white canvases around the gallery, spectators will notice that the first coats of paint on the canvas’s original black were bright teal before layers of black paint and colorful pink and yellow stripes were added. Bright red diagonal lines formed a grid in the center of the canvas. Callis said the black paint represents society’s collective reality changing due to the constraints of the pandemic; the color stands for the joys amid uncertainty and hurt within communities that he saw amidst the grief of the coronavirus.

“I wanted the big paintings to give a place of pause and grief and that it’s something a little bigger and more colorful,” said Callis. “Someone described it the other day as if … this is like the larger community that holds me, it’s something that’s bigger than I am and bright and coming at me.”

SAINTS & CLOWNS

The exhibition also features three sculptures — part of his previous exhibition at the Long Beach Museum of Art — titled “Casting Nets.” Under the name of “Saints & Clowns,” Callis hopes that the three pieces give tribute to church reformers such as St. Teresa of Avila and St. Francis of Assisi.

“I introduced these works and a number of others and then the show, [Casting Nets], ended and two weeks later, the whole world shut down,” said Callis. “So in some sense, it’s like [the artworks] places in the world got cut off. But for me it was kind of the thread [between all the works]. This was what I was doing right before [the creation of the other works] and you see it in the other work.”

Callis expressed his hope that the stations and artwork around the exhibition would give spectators a safe space to grieve and lament. As he talked with people visiting the gallery, Callis said he found joy and contentment in knowing visitors felt comfortable sharing their grief with him.

“A third of the psalms are grief,” said Callis. “Grief and lament poems in the psalms are like an integrated faith and integrated human being [experience]. One where grief and lament and vulnerability [have] a place in our conversation.”