The scene on stage began on a rainy day as people huddled underneath a church overhang, waiting for the drizzle to stop. It was there that Dr. Henry Higgins, a world-renowned linguist, came across fellow linguist Colonel Pickering, and the both of them became fascinated by the cockney flower girl Eliza Doolittle. Higgins accepted a bet that he could pass off the flower girl as a duchess after six months of speech training, and from there the play launched into a story that explores themes of change, respect and human kindness.

“Pygmalion” is a play written by George Bernard Shaw and named after the Greek mythological figure. In myth, Pygmalion was a sculptor who fell in love with a statue he created named Galatea; with the divine aid of Aphrodite, goddess of love, the statue came to life and Pygmalion married her. Similar themes of transformation and change flow through Shaw’s “Pygmalion.”

Shaw’s play first premiered in Vienna on Oct. 16, 1913 and was later adapted into the musical “My Fair Lady.”

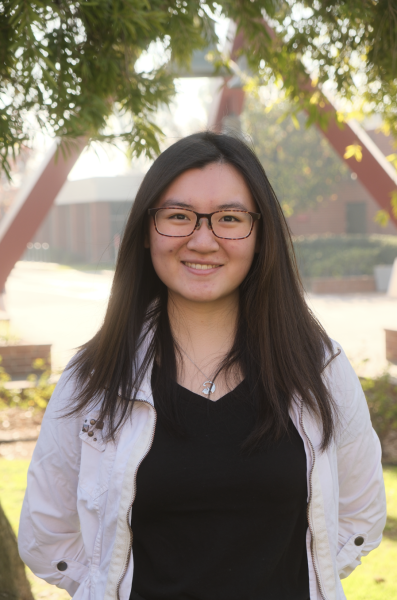

David Fung, a sophomore Bible major, and Emma Broyles, a sophomore screenwriting major, co-directed the show for Torrey Theater, which the cast performed the evenings of March 17, 18 and 19. Fung and Broyles shared what they learned from the experience.

This article was edited for clarity and precision.

How was the process of choosing “Pygmalion,” and why did you choose it?

David Fung: I chose “Pygmalion” back in November when “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” was still going on. The reason I chose it is because a good friend of mine told me about it. He was like, this is a good play, you should research and learn about it. Like, okay, and I looked into it, and I discovered it had a lot of history and really was impactful. And then I started talking to Emma. And she was like, “I was in this play!” and I was like, “Oh, then we definitely have to do it.”

How would you describe Pygmalion in three words?

DF: I like to think of it as a question, like, ”What is change?” To me, that is what Pygmalion is. That’s what Shaw is poking at. Almost all the characters are poking at change, like, “do you understand what change is?” For example, Mrs. Pearce and Miss Higgins — they’re really pushing and asking Mr. Higgins: “do you think about what this is gonna do?” And then [Mr.] Doolittle understands change in a very different way, like changing between classes; he understands that is an alteration of who he is, and no one else sees that.

Emma Broyles: It’s also about internal and external changes, how one thing does not necessitate the other. Just because [Mr.] Doolittle changed the outside doesn’t mean he changed on the inside. [Mr.] Doolittle is fundamentally the same even though he’s come into money. It doesn’t really change any of his mannerisms. And then Eliza, for instance, in the first half of the show, has an external change, and the internal change is very underneath the surface. But then in act five, you really see the internal change come to fruition.

What is a favorite experience or a moment from either the production process or the performance itself?

DF: One favorite moment was the snapping applause at the end of act five in the first show. It really brought joy to my heart because it really showed that the play was more than just a play. It was more than just a comedy, entertainment, entertainment, and it meant something to the audience. And so that was just — that brought me so much joy.

EB: “Pygmalion” is a risky show to do, because it doesn’t have anything that everyone expects. It’s a drama, not a comedy, even though a lot of the lines play like comedic lines. And I was worried because people have to sympathize with Eliza and dislike Higgins. Elijah Price [who plays Higgins] is extremely likable, and his character is not. And so when Eliza stands up to Higgins, and everyone is like, “yes,” because she’s like cutting her ties with him — that was a very proud moment for us.

What was something you found challenging during the experience?

EB: One thing was trying to help people reach into their emotions, very broad emotions — because Pygmalion is an incredibly emotional play. It relies on all these emotional beats. In some ways it relies more on how the lines are delivered than the lines themselves.

DF: I feel like that’s especially true with the Cockney people, like in Act Three. Eliza starts speaking very formally, and if you don’t speak that way, the line isn’t funny and you lose all of Act Three. The goal is to take the emotion out of Act Three, because every other time Eliza is constantly pumping emotion through her lines. If she doesn’t pump out her emotions, then Eliza doesn’t feel like her character. And that goes for all the Cockney people: if you don’t have emotions, you don’t have Cockneys.

It’s hard for some people to connect into emotions, and for other people, it’s hard to portray your emotions. And when you’re up on a stage, that can be very vulnerable and exhausting. And so a lot of people just don’t want to participate in that, and so we try to push people into understanding that, hey, this is a good thing to do, it’s beautiful, you should partake in it.

What has Pygmalion taught you about being a relational human being?

DF: A big thing is relationships. Firstly, Pygmalion is not a romance. In a lot of media you get nowadays, with relationships, either everything is romantic or it’s not romantic at all, or everything should be pushed towards the romantic. But a lot of what a lot of we see nowadays is like romantic love. And Pygmalion is in no way romantic. It’s clearly distinguished that it’s not romantic love, and the only romantic love is between Eliza and Freddy and you really don’t get to see progress at all.

And so how that highlights the way we treat our friends and the people we hang out with, the way we interact and respect our parents in a bunch of different types of relationships, really brought light to the questions, what does it mean to be a good friend? How do you treat strangers? What does it mean to invest in people and want to change them, like how we’re doing to our actors? So how Pygmalion widens the scope to more than just romantic relationships was really impactful in the way I view relationships and so that was a big way.

EB: For me a lot of this goes back to a relationship with the self. For example, like how Eliza has this transformation from being a flower girl to a self-respecting lady, and being able to make peace with the different pieces of yourself and how you’re only able to make good relational decisions — like her decision to leave Higgins — out of a knowledge and understanding of who she is. It’s both in the sense of, “I came from the gutter, and this that will always be part of me,” but also, “I now have learned these things that have grown me and shaped me.”

Also, paying respects to the people in your life who have taught you is, I think, really important. Teachers and professors have played a huge part in my life, but it’s not just the teaching and the refining of a person, it’s the cultivation of the person as a whole, which we see Pickering do with Eliza. I think that’s really important. We see that in how Eliza, in the last act, is able to pay respects to Pickering and tell him, you were the one who really triggered this transformation in me because of how you treated me. The importance of kindness is clear in the show, but it’s not just kindness in the way that you let anyone get away with anything — it’s like a self-respecting kindness.