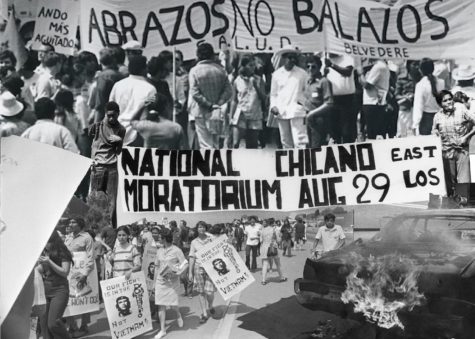

Tens of thousands of protestors filled the streets of East Los Angeles and marched down Whittier Boulevard on Aug. 29, 1970. They carried signs which read “abrazos no balazos” and raised their fists to represent Chicano power.

The demonstrators made their way to Laguna Park and violence broke out when police entered the scene, declaring the demonstration illegal. More than 150 protestors were arrested and four killed on that day, 50 years ago, including Ruben Salazar, a well-known activist within the Hispanic community and reporter for the Los Angeles Times.

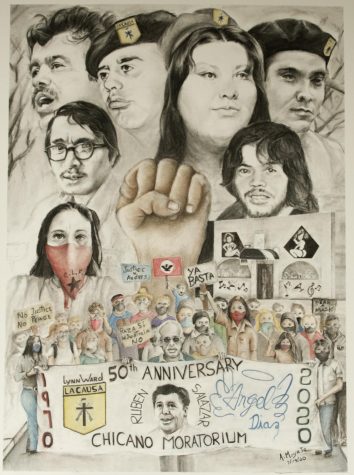

CHICANO MORATORIUM ART EXHIBIT

Mexican Americans celebrate and remember the Chicano Moratorium each year. Kitada was invited by his cousin, Abram Moya Jr., curator for the Chicano Moratorium art exhibit, to participate in this year’s showing.

Kitada, once a photographer for the Orange County Register, noted the parallels between himself and Salazar. Both of the men are of Hispanic heritage, immersed in Los Angeles and journalism. Encouraged by his cousin, Moya, Kitada jumped at the chance to engage in his heritage and began to dig into the history of Chicano activists in Southern California.

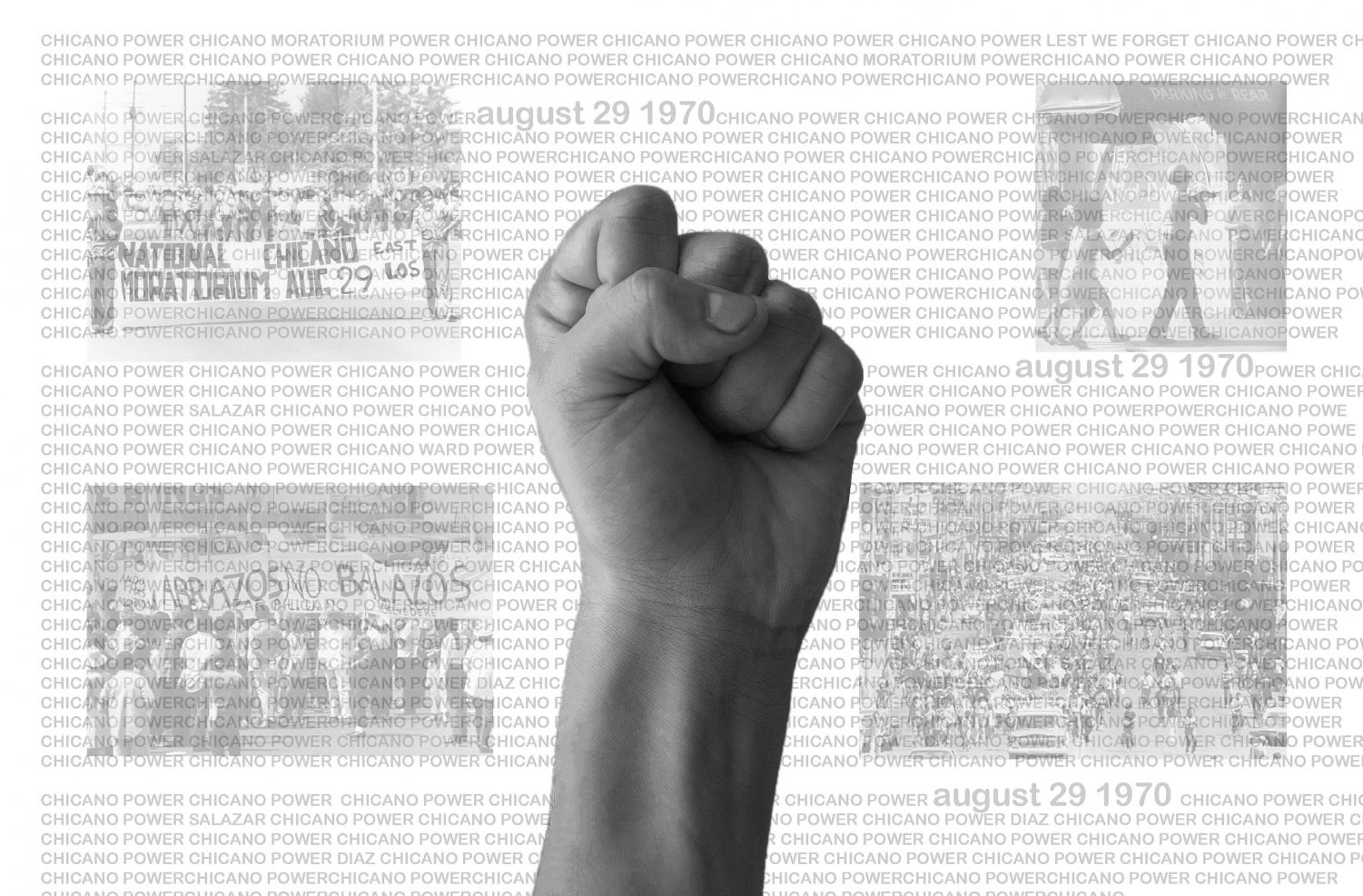

“LEST WE FORGET”

Kitada created a fine art piece titled “Lest We Forget” which repeats the words “Chicano power” over and over across the page. He explained that the brown fist at the center is the logo for Chicano power. Kitada listed the names of three people killed during the protest, including Salazar, hidden among the repetition of Chicano power.

In the piece, Kitada placed four images around the fist. Each image is set to a specific opacity to represent events of the day. The picture of the Silver Dollar Bar is at 42% representing Salazar’s age when he was killed. The other three images are set at 29% in order to commemorate Aug. 29, the date of the Chicano Moratorium.

RECONNECTING THROUGH ART

Raised in the states by a Mexican mother and Japanese father, Kitada found himself relating most closely with an Americanized culture.

“We were raised very American, you could say,” Kitada said. “So I’ve had to reconnect with my roots at different points in my life after my childhood.”

Moya was the first to encourage Kitada to understand his heritage and roots. According to Kitada, Moya has been the family activist for as long as he can remember, even marching with Cesar Chavez, another historic figure in the Hispanic community.

Kitada, with the help of Moya, delved into a rich familial heritage through art. The exhibition allowed him the opportunity to educate himself more on Hispanic culture in the past and how it relates to his family now.

JOURNALISTS IMPACT THE MOVEMENT

Salazar was the first mainstream, Mexican American reporter to cover Hispanic communities and paved the way for the Hispanic reporters of the future. Laguna Park was renamed Salazar Park in honor of Salazar’s commitment to the Chicano community, whom his death greatly impacted. As a Hispanic photographer, Kitada believes he stands upon Salazar’s shoulders today.

Even though these events took place many years ago, the Chicano Moratorium and Salazar continue inspiring and impacting the Hispanic community today. Many still seek justice for Salazar and hope to continue his legacy as journalists and reporters.