This story was originally published in print on Nov. 1, 2018.

Though there is not much evidence to support the claim, it is often assumed that college campuses are ground zero for sexual assault. What lends legitimacy to this claim is that colleges do sit at the intersection of dangerous crossroads: inexperienced youth, free flowing of alcohol and the universities’ reliance upon their own judgement instead of appealing to legal action.

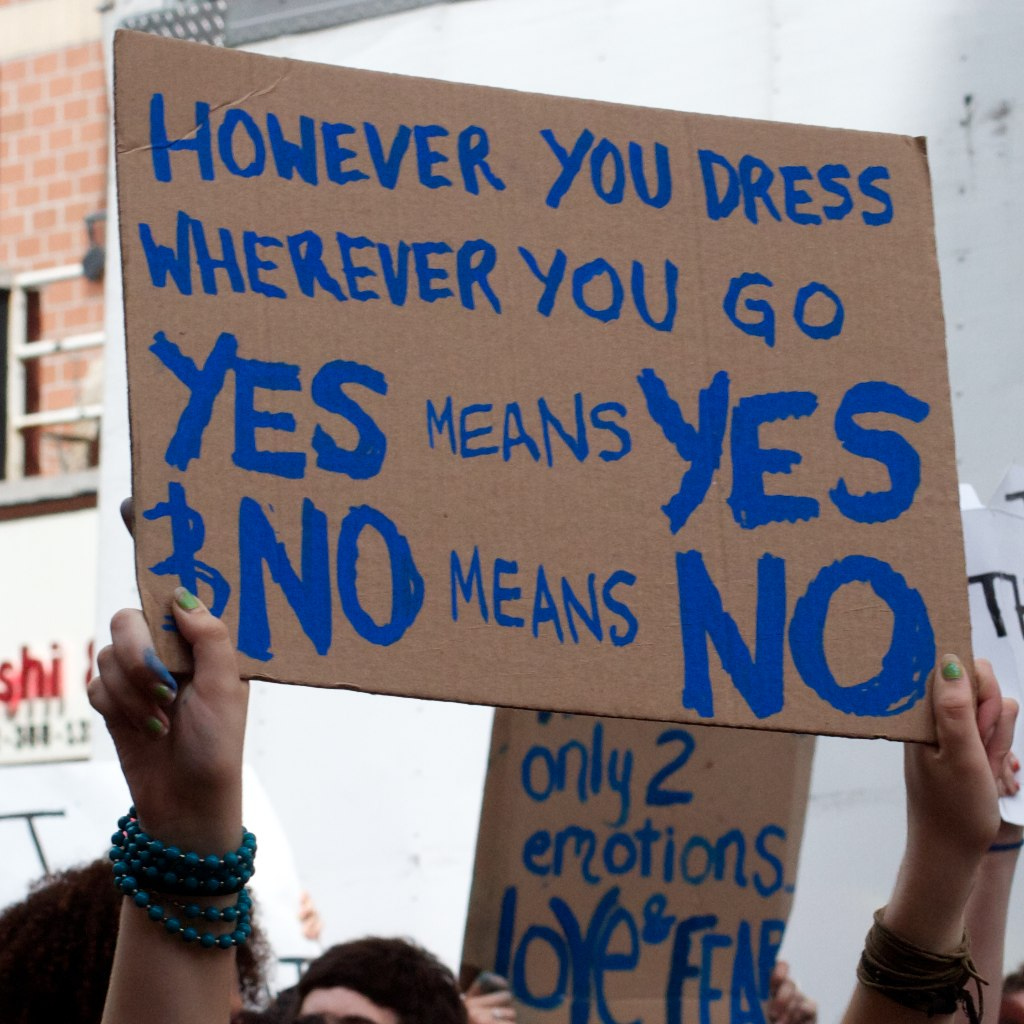

The common approach to combating sexual assault has been to reinforce the motto “Yes means Yes”. However, in light of the #MeToo Movement, the Harvey Weinstein case and a plethora of other prominent examples of sexual assault, one can persuasively argue that verbal consent is insufficient. Something more than consent is required. According to a recent study by professors at Redeemer University College and Harvard University, evangelical campuses seem to fare better than secular campuses, and much of it has to do with how Christians value restraint over consent.

THE CASE AGAINST VERBAL CONSENT

When California drafted the first version of “Yes means Yes,” it had a clause which established verbal consent as the minimum requirement for sex. However, the bill received massive pushback on two fronts: intrusiveness and effectiveness.

The argument from intrusiveness is most forcefully made when trying to interpret the extent of active verbal consent. Despite producing a legal nightmare, the legal requirement of continuous verbal consent during sex is unprecedented in its intrusiveness.

The argument from effectiveness is simply an argument that sex often happens behind closed doors. Sadly, if people are willing to lie about sexual assault, what prevents them from lying about consent during sex? What does verbal consent actually provide as an additional form of protection? Unless we are willing to accept that convicting innocent people and overturning our concept of justice are necessary costs for progress—as Ezra Klein, editor and co-founder of Vox, suggested—there seems no way to produce enough evidence to convict sexual assault based on verbal consent.

California eventually modified the Assembly Bill, eventually signed into law as Senate Bill 967, to define consent as “affirmative, conscious, and voluntary agreement to engage in sexual activity.” No verbal agreement, simply a clear and conscious agreement—a murky standard at best.

THE CHRISTIAN SOLUTION IS VIRTUE

According to a recent article by Christianity Today, the aforementioned study “suggest[s] that the most significant disparities between Christian and public or private institutions correspond to the biblical convictions at the core of the community, from shared morality to their approach to gender roles.”

This has been referred to as the “moral communities thesis” and suggests that men and women in these communities internalize and act according to criteria that is part of their faith’s traditions and teachings, resulting in reduced cases of sexual assault.

These internalized criteria are, to put more plainly, habits of virtue for proper sexual conduct.

THE DEBATE BETWEEN THIN AND THICK VIEWS OF SOCIAL ETHICS

The debate, however, seems to revolve around two radically different conceptions of sexual ethics. At one end, the secular proposal is a form of sexual minimalism, or thinness concerning sexual morality. These theories search for principles that require the minimum level of commitments necessary for the most broad social acceptance—for example “Yes means Yes.” However, these extremely broad principles fail both to provide a clear understanding of sexual ethics while also failing to provide clear protection from sexual assault.

To the contrary, Christian virtue ethics requires a much deeper, or thicker, moral requirement. As C.S. Lewis mentioned, “When two people achieve enduring happiness, this is not solely because they are great lovers but because they are also—I must put it crudely—good people; controlled, loyal, fair-minded, mutually adaptable people.” Christian virtue ethics argues that sex is to be engaged in not only under certain conditions but also as a proper expression of moral virtue. We must be good people.

Despite the motivation to adopt a “thin” view of ethics and its initially wide social appeal, a thin view of ethics does not deliver what everyone desires in our most intimate relations—love, faithfulness, self-control and goodness. As G.K. Chesterton once wrote, “In so far as religion is gone, reason is going.” When it comes to sexual ethics, in so far as virtue is gone, respect for sex is going.

This is not an argument that Christian universities such as Biola are perfect, but that Christian universities are on the right track. We must stop pretending that sexual consent is the whole picture of sexual ethics. If we want progress in sexual ethics, we must return to a more complete version of sexual morality—a Christian virtue ethics that focuses on moral formation and not mere consent.

The answer to the disaster of “Yes means Yes” is cultivating moral virtue.