This is part two of a three-part series on mental health. Part one can be found here. Part three will be published in print and online on Thursday, Oct. 18.

Moses Sambo loved to be around people.

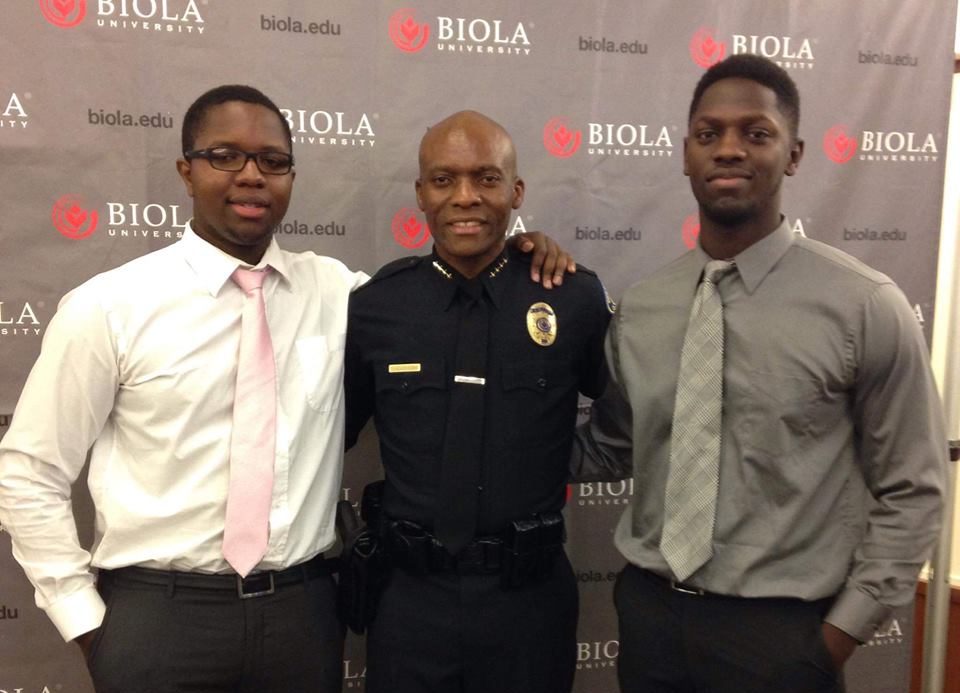

He was kind, goofy and enjoyed jokes. Standing just taller than his uncle, Campus Safety Chief John Ojeisekhoba, he was at the perfect height for his cousins to climb on. Since his parents lived in Nigeria, he spent Thanksgiving, Easter and Christmas at his uncle’s house. The kids would rush him, swarming around their older cousin with childlike joy.

He was also smart. A communication studies major, Sambo graduated from Biola in May 2016 alongside his peers. They had seen him carry the Nigerian flag during the 2015 Missions Conference parade, when he had volunteered after noticing that his country had not been represented in the ceremony the previous year.

Throughout his college experience, he was like a son to Ojeisekhoba, often listening to his advice on how to succeed as a student. After his graduation, in the late summer of 2017, Sambo called his uncle, whom he had not seen in some months. He made plans to visit Ojeisekhoba, but never came, which the chief says was not abnormal.

On the night of Sept. 30, 2017, Ojeisekhoba received a call from the Los Angeles Sheriff’s Department.

“Over the years, I have written procedures and given many presentations about the subject of mental health. Yet, I never saw it coming,” Ojeisekhoba said in an email. “I never knew that my very own nephew was experiencing depression. Never did I ever imagine that he would take his own life.”

Because Sambo’s parents were in Nigeria, Ojeisekhoba and his wife had to do the primary planning of his funeral. He says the most difficult part was having to tell his sister, brother-in-law and children that their beloved son and cousin had died.

“I have to be strong for the family… because I’m the eldest here, in the United States. But deep down, it was hurting like hell,” Ojeisekhoba said.

It has been just over a year since Sambo’s death, and while Ojeisekhoba says the family can now celebrate his life, the pain still remains. Their only comfort, he says, is that Sambo loved God and that his family will see him again in heaven.

A NATIONWIDE PROBLEM

As Campus Safety chief, however, Ojeisekhoba must continue to deal with crisis situations involving students. He says that during the first six months after Sambo’s death, he was so sensitive to mental health issues that he had to rely on his team to keep him from overreacting when a call came in.

He is dealing with a nationwide problem. The suicide rate for 15 to 24-year-olds has been steadily increasing since 2000: from 17.1 suicides per every 100,000 deaths to 20.5 in 2016, according to the National Center for Health Statistics. Now, Ojeisekhoba is looking for ways to better help students in traumatic situations.

If Campus Safety receives a notice about a student exhibiting thoughts of suicide, personnel will go to the general area and support the Resident Director. Ojeisekhoba says officers do not meet with the student directly, as the sight of the uniform may make an already traumatic situation worse, but remain on standby if harm becomes imminent.

THINKING ABOUT THE AFTERMATH

Physical safety is only part of students’ well-being, according to Ojeisekhoba. Student Development and the Biola Counseling Center can help the student with their mental health after their immediate safety is secured.

“Our response needs to be student-centered, our response needs to be not focusing merely on the present. We have to think about the aftermath as well,” Ojeisekhoba said.

While Ojeisekhoba understands why law enforcement must place individuals with suicidal intent in handcuffs, he believes that the same practice can cause more trauma when the individual is a student on a college campus. In order to better care for both the physical and mental health of students, Campus Safety has worked with the LASD’s Mental Evaluation Team, which has personnel in plainclothes who are specially trained in mental health awareness.

Furthermore, he recently reached an agreement with the LASD that will allow Campus Safety to contact the MET directly, rather than having to wait for the deputies to request additional units. Ojeisekhoba believes this will allow for a more appropriate support of students with depression or thoughts of suicide.

Throughout this process, he returns to thoughts of his nephew, Sambo—a young man who loved to make jokes and be around people.

“It’s personal now, [more] than ever before. In my role as chief, yes, it was personal because I care about students. I went here. But then my nephew [killed himself],” Ojeisekhoba said. “I did explain this to the… LA County Department of Mental Health unit, why this meant a lot to me, why the agreement meant a lot. Does it make me ultrasensitive? Oh, I admit, yes. Because the last one year has been very, very painful.”