Occasionally, there comes an auteur, a skilled and sensitive artiste, who operates not unlike a machine. There is a Vincent van Gogh, whose every brush stroke seems to encapsulate creation’s utmost potential. There is a James Joyce whose every turn of phrase begets more wit and profundity than most are capable of in their entire lives.

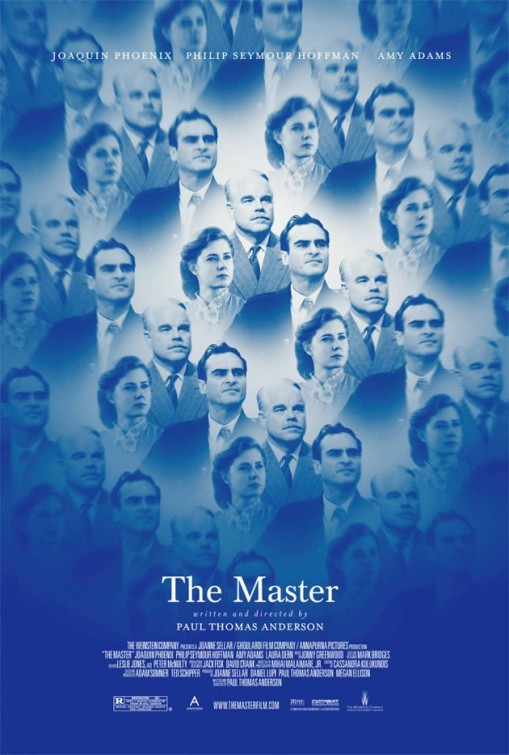

These men are enigmas, thoroughly unbelievable specimens capable of disarming would-be creators by involuntary intimidation. Paul Thomas Anderson is a wizard such as this and “The Master” is another awe-inspiring canvas he can catalog on his shelf of utter glory.

Admittedly, this praise may sound hyperbolic, but “The Master” is getting rave reviews across the board. It is the story of two larger-than-life, indecipherable and incredibly curious characters: Freddie Quell and Lancaster Dodd.

Quell, Joaquin Phoenix’s first role since his now legendary staged meltdown, is a World War II veteran plagued by problems aplenty. His motives are obscure and his morals either nonexistent or wholly unique to his own bizarre personage. When he isn’t lashing out in anger, he’s fantasizing or attempting to execute sexual escapades; when he isn’t dancing along the line of Freudian fancy, he is mixing strong drinks made up of alcohol and camera darkroom chemicals. The man is astray and confusing.

Lancaster Dodd is played by the always Oscar-worthy Philip Seymour Hoffman. Much buzz was generated by the character’s similarity to Scientology founder, L. Ron Hubbard — an unavoidable comparison after viewing the film. Dodd is rich, enigmatic and in possession of a Fort Knox-sized stash of charisma. When asked by Freddie who he is, he replies like a man firmly aware of his place in the universe.

“I am a writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher, but above all I am a man; a hopelessly inquisitive man, just like you.”

The lives of the two begin to interplay in the larger context of Dodd’s cult, The Cause, and its rise to popularity. This makes the viewer’s religious impulses whir with questions. What brings a virtual wild man like Freddie to a collected, albeit hypocritical, persona like Dodd? Freddie made it through WWII with nothing but confusion and frustration left to his name. War has a tendency to eradicate any common social categories by which to make sense of the world. In the face of such violence and trauma, being told you are a trillion-year-old spirit and able to achieve higher consciousness can become a source of joy instead of mere caustic laughter. Dodd presents answers when an entire generation had nothing but questions.

It would behoove the potential viewer to know that this is not a film for the easily offended or faint of heart. Freddie’s sexual fixations make up for a lot of the film’s thematic study and one scene in particular features a lot of gratuitous, almost nonsensical female nudity. Anderson has never been a stranger to potentially offensive material. His second film, “Boogie Nights,” was a panoramic wide angle shot of very human porn stars, and “Magnolia” features Tom Cruise as a misogynistic seduction seminar leader. No Christian viewer can be blamed for not watching the films on principle. Still, it is Anderson’s uncomfortable depictions of the darkened human condition that reveal his seemingly deeper motives: to show what redemption can mean for a man at the end of his rope.

“Magnolia” and “Boogie Nights” may be disturbing at moments, but they end with hope, grace and happiness peeking over the hills. “The Master” is even more unsettling for its refusal to answer the questions it raises. Freddie and Lancaster both occupy an endlessly unsettling space of indecipherability. Just when they seem to be ironing out their respective flaws, they lurch backwards into another act of violence or manipulation. Freddie seems to be unable to decide whether he feels more trapped and chained by his own vice and instability or by The Cause, which promises deliverance. Lancaster’s own web of fanciful, religious deceits serves to help his followers but further constrain him into repression.

Beyond its superb acting, characterization and plot, the film is just a beauty to look at. Every single shot is composed with the care of a mother hen nursing its chicks. Each could almost be a still life hung upon a wall for decoration. Anderson makes his colors pop and trains the camera on the faces of his lead characters, leading the viewer to wonder: What could possibly be going on inside their heads in the first place? Radiohead guitarist Jonny Greenwood writes his second score for the director here and it is even better than his previous work on “There Will Be Blood.” It haunts and accentuates along with each line spoken and each visual captured.

“The Master” is artsy and, at some times, foreboding. It is hard to understand and difficult to watch. It’s also humorous and engaging, a character study and exposé of pleasing visual aesthetics. Other fall films may pack a more immediate entertainment value but this is one for the history books.

Note: "The Master" is rated R for sexual content, graphic nudity and language and runs 137 minutes.