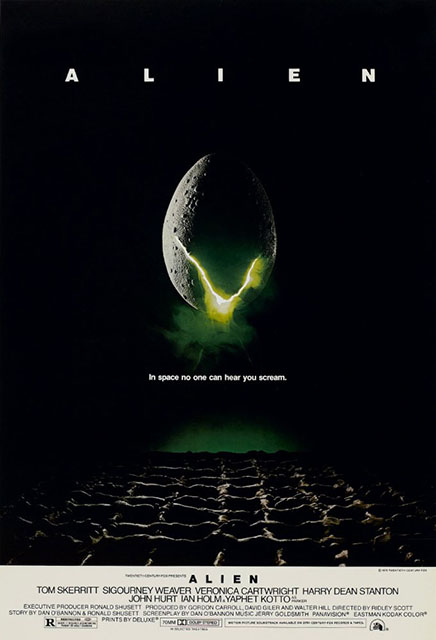

Ridley Scott’s 1979 sci-fi horror masterpiece “Alien” holds up 38 years later as a truly disturbing thrillride. Whether one looks at H.R. Giger’s pseudo-sexual design of the deadly and ruthless Xenomorphs or Nick Allder’s unquestionably gross special effects, few films have achieved this balance of visceral macabre, isolation and terror. Although considerably less enduring, Jerry Goldsmith’s score played a vital role in constructing the movie’s supremely chilling atmosphere. His avant-garde epic uses both traditional and experimental flourishes to create an aural monster to coincide with Giger’s otherworldly abomination.

a far cry from the original

One of the biggest dilemmas horror movies face today includes their over-reliance on jarring crescendos and sudden pace changes to emphasize cheap jump-scares. Even the trailers for “Alien: Covenant” — scheduled to release this Friday — feature generic piano music and explosions of sound, a far cry from the original film’s stunning score. Goldsmith saw what would eventually become the theatrical release of “Alien” by himself and experienced its insurmountable dread firsthand. He saw how the film’s extreme slow burn effectively upped its unnerving qualities and wrote his score to accentuate those elements. What results is a truly frightful experience in its own right, and a lesson in how music can and should be used in a film.

The main title emphasizes chilling ambiguity right off the bat. With unexpected brake drum hits chiseling into ascending and descending lines, it builds tension without resolving it — allowing the film’s scenes to cut the tension like a knife. Goldsmith sets out to accentuate what he experienced with “Alien,” and succeeded through an intuitive understanding of the film’s antipathic beauty.

Each of Goldsmith’s compositions evoke the scenes after which they are named, but the score transcends lesser pieces by capturing their underlying emotional gravity. “Face Hugger” uses gurgling noises, vocal whistling and sudden trills to capture both the pulsating creature and its sudden spider-like leap onto the victim’s face. In the same way, the hair-raising ambience, spaciously echoed percussion, staccatos and shrill dissonance of “The Alien Planet” contrast a sense of wonder with creeping malice and unexpected demise. This score captures both the science fiction and the horror element of “Alien” as Goldsmith evokes both the majestic and nefarious nature of extraneous life. Such a multilayered approach has become uncommon in Hollywood movies.

a near-perfect engenius milestone

Modern films come under tremendous pressure to make the right amount of money for the right people, making their direction, editing and design a game of playing it safe without becoming too obviously derivative. Scott and Jed Kurzel, musical director of “Covenant,” now have the daunting task of returning to a world of their design and maintaining their vision in the midst of executives telling them how to do it. Vision gives way to box-office potential, making most blockbusters competent at best. What made “Alien” a beautiful work of art now seems bad for business, but that film maintains remembrance because the creators took chances and stayed true to their passion.

Goldsmith’s score stands as a pristine example of why movies need creative flow to reach their potential. These unorthodox compositions certainly dilute expectations, but also breathe life into an original cinematic experience. He did not set out to check off boxes, but to bring a world to life. While recent advances in special effects send visual possibilities into space, what makes a film stand the test of time is an organic creative process in which the creators do what makes sense to them. This made “Alien” a near-perfect engenius milestone, and Hollywood’s refusal to adopt it will continually affect its artistic integrity.