When I first asked Ron Hafer to meet with me, he said Biola had been on “Ron Hafer overload.” But he’d do it – if only for a chance to talk with a student. That probably explains why, when I asked him his favorite part about being the university chaplain, he looked me directly in the eyes and said, “This, by far, by far.”

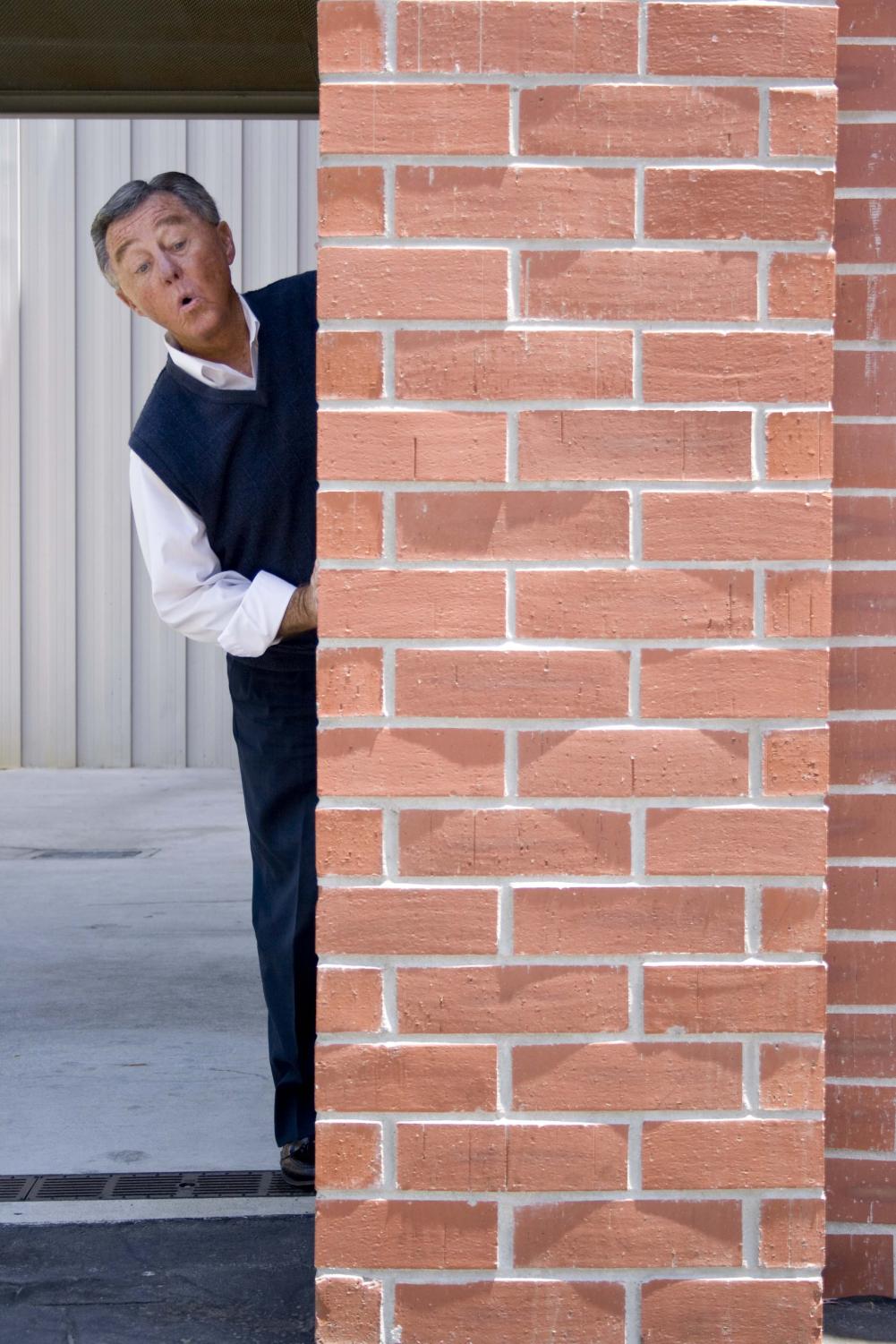

As I sat at a table by the fountain, some students passed by on their way to classes while others sat by the fountain, studying for the last time before their tests. Hafer came toward the fountain from the bell tower in his cream shirt with the collar unbuttoned under his maroon sweater vest. He gave me a hug, and apologized for being late; he’d just come from talking to a student whose life would quite possibly have fallen apart if Hafer hadn’t stayed to listen to him.

Pulling up a chair in front of the roses, Hafer told me that a fountain visit with a student was a favorite routine of his. He said if he wasn’t meeting with me, he would have flagged down one of his regulars.

“The first hour of my day for the last several years, I just come here, or around Eagles Nest where students are, and hang out,” said Hafer. “And every day, every day, without exception, I have a chance to interact.”

Hafer stopped and pulled a 4×6 card out of his Bible. “One, two, three, four, five, six, seven,” he said, counting the names of all the people he had talked to the morning before.

“And you will be on here next,” he said, scribbling down my name. The bells rang in the distance and he waited for them to fade before talking again.

“I’m going to miss that lovely gong,” he said.

Since his retirement chapel, where he received a white mailbox full of letters from students, the flow of mail has not slowed down. The large mailbox sits in his office and almost every time he returns, he finds the red flag up, indicating that students have left everything from cards to suckers for him.

Hafer paged open his Bible and pulled out another note card. He said this note was a recent favorite and that it would make it into the book he’s planning to write about his time at Biola. He turned the handwritten card over and read it out loud.

“‘Dear Mr. Hafer, I’m finishing my freshman year at Biola, and when I first got here I was painfully lonely,’” read Hafer. “‘About a week into the fall semester, you were roaming the cafe saying hello to all the students. You walked right up to me and introduced yourself and asked my name, taking me by the hand and declaring that now you’d made a new friend. Since then, you have introduced yourself to me no less then five times and every time you said to me, ‘Oh, now I’ve made a new friend.’ I’m sure, Mr. Hafer, you have fleets of friends, but I thought I should inform you that at least six of them are me.’”

While the mail is a welcome thing now, Hafer said he might not have always taken it so well. “Early on, I had way too much acclaim and I loved it and it went to my head,” said Hafer.

What made him change?

“I think life,” said Hafer. “Seventy years on the planet beats you up even if you’re Billy Graham.” And the changes that happened weren’t always easy. “I needed God to just kick the tar out of me.”

He waved at a few students as they walked by. It’s clear that students at Biola love Hafer, but I really wanted to know why Hafer thought the students love him. His hands rested back on the table and he glanced around, pondering the question.

“Some of that is probably better answered by students whom you can ask,” he said, shaking his head. But then he got serious – serious about that fact that it’s necessary for him to be funny. And that sometimes means taking shots from people about his sweater vests or eternal tan and learning to enjoy it.

“Maybe I’ve had some effectiveness because I’m lighthearted,” said Hafer. “I don’t take myself too seriously and maybe I’m approachable.” Beyond that, Hafer’s strategy is to get to know a few students, rather than the masses.

“I know that I probably won’t ever meet them all,” said Hafer, “but that’s why I make an effort to go sit and be where students are.”

All the people that Hafer has met in the past 42 years of being Biola’s chaplain, including the woman he met six times in a row, will not go undocumented. Besides hanging out with people, Hafer is writing a book about his history at Biola with glimpses of the many students he’s spent mornings with over the years. Even though Hafer doesn’t officially have a position in the future, he said he still might be found sitting with his coffee by the fountain and waiting to talk with students.

As I sat outside at the table with him and watched students high-five and hang-ten him, I realized that the reason everyone loves Hafer so much is because he takes time to sit and casually talk with students like me.