Biola’s student body is composed of students from a wide array of denominational and spiritual backgrounds, ranging from Evangelical, Baptist, Anglican, Non-denominational, Catholic and Orthodox traditions, though high-church students remain in the minority. This diversity, one of Biola’s strengths, can also lend to a quiet sense of unease in places where theology and practice meet. This convergence is specifically found in the implementation of contemporary, or new age worship and has sparked concern among certain students from across these varying traditions. This has prompted many to reflect on their own convictions in light of Scripture.

Although the university offers five chapels each week, the worship styles remain strikingly similar, unified under a contemporary evangelical model that prizes accessibility, informality and spiritual engagement. For students whose traditions emphasize liturgy, reverence or theological reflection, this uniformity can feel alienating and theologically unsatisfying.

Many high-church students find their convictions about worship not only unappreciated but unrepresented. Their discomfort raises an important question: what is the true purpose of worship, and is Biola facilitating it rightly?

At its core, Christian worship is meant to reorient the believer, to turn the whole person, mind, body, and spirit, toward the glory of God.

“Worship and music ought to point the whole person and the whole body to God,” senior screenwriting major Audrey Schnell expressed shared “It does the horizontal level of unifying not only the individual in their soul, in their reason, in their appetite, in their spirit, but also unifies the body of Christ, recognizing that these people are here with them and not for them, but for God.”

Schnell’s reflection illustrates that worship is not an emotional outlet or performance, but an act of union – an aligning of our entire being with God’s holiness. In centering worship upon the divine rather than the self, the Christian encounters not mere euphoria, but individual and communal transformation.

Contemporary worship often strives to create an atmosphere of accessibility and excitement. With these values in mind, theological substance and the recognition of God as holy and above are often cheapened, or seen as undervalued by those unaccustomed to the more contemporary style. The lyrics of many modern worship songs tend to revolve around the believer’s feelings and experiences of love, longing, and other emotions, rather than on the nature, promises, and redemptive work of God. Such a focus can subtly reshape the purpose of worship, making the worshipper the subject rather than the Lord. When music fixates on emotion rather than truth, worship risks becoming a search for spiritual stimulation rather than an act of holy reverence.

Senior philosophy major Richard Wilson, who recently joined the Eastern Orthodox Church, noted the imbalance he feels in many evangelical worship settings.

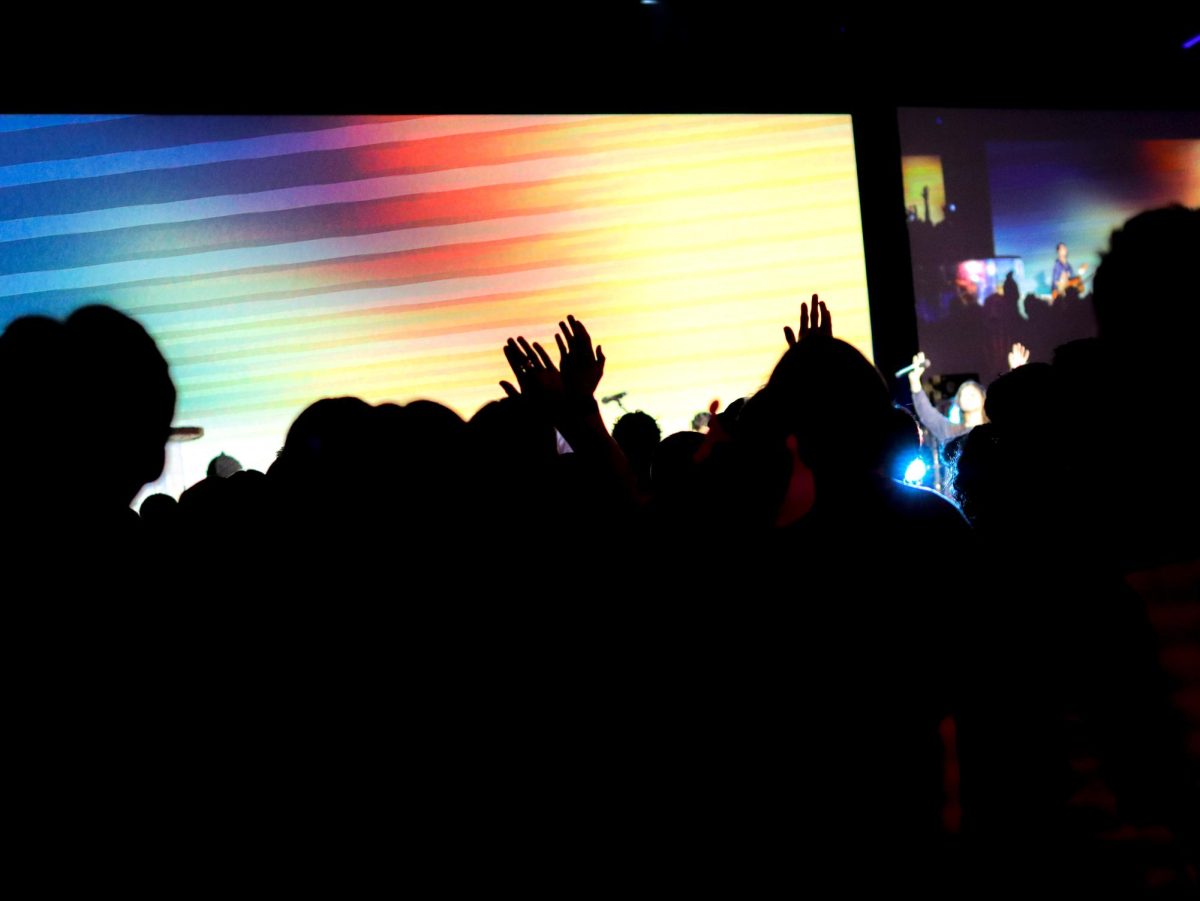

“Evangelical music often communicates that we’re having fun, partying, going to a concert,” Wilson said. “It’s more informal and fun.”

His observation points to a broader cultural trend, worship that mirrors entertainment rather than sanctification. When the goal becomes emotional engagement or audience enjoyment, the sacred purpose of worship is diminished, replaced by something transient and self-referential.

Schnell also highlighted what many view as the central defense of contemporary worship: accessibility. Much of contemporary worship can be defined by simple choruses and melodies accompanied by lyrics that align with current lingo and phrases that mirror our daily language. This musical approach to worship is often defended in the name of accessibility with the assertion that it functions as an evangelical strategy.

“A lot of the argument behind this kind of chapel music, in churches especially, is the accessibility factor,” she said. “You have to strengthen the beliefs towards something that is good and not cheapen that for numbers.”

Her words capture the tension at the heart of the modern evangelical dilemma. In seeking to make worship inviting and emotionally resonant, there follows an inadvertent cheapening of the message of Scripture as a whole. Accessibility need not mean simplification, for the beauty of the gospel lies in and depends upon its mystery, reverence, and depth.

Wilson contrasted this with his own experience in the Orthodox Church, where worship is seen as an act of continuity with the temple worship of Scripture.

“We look at worship and church services as a way of carrying on the tradition of temple worship,” he said. “While we believe that Jesus recast sacrifice in a new light, we also believe that he kept the tradition.”

This continuity, rooted in the sacredness and kingship of Christ, offers a vision of worship as participation in something timeless, not merely performative or emotion. And yet, Wilson is careful not to dismiss evangelical expression entirely. “There is a place for both. It’s important to hold both.”

His perspective points toward a hopeful balance, one that honors the vitality of contemporary worship while reclaiming reverence, depth, and substance.

How might Biola embody this balance? Wilson suggested that even small steps toward liturgical diversity could foster deeper unity.

“Fives seems like a halfway house, that’s great. Can we have one that is more traditional?” he said. “Can we step into a more reverential, liturgical space, even just once a month. We’re a minority, but we’re a minority that brings part of the body of Christ. There is a space for us even though we’re a small minority.”

Such a proposal is about more than preference, but conviction and formation. It calls Biola to see the minority among them in a way that honors their spiritual and theological convictions. Worship undeniably shapes what we love and how we live. If Biola seeks to form students who worship in spirit and truth, it must also cultivate spaces where different expressions of faith can point together toward one God.

True worship, whether sung in contemporary choruses or ancient liturgies, must ultimately lead believers to adore Christ as king, not elevate the self as center. As Biola continues to wrestle with its evangelical identity and denominational diversity, perhaps the question is not which style of worship is “right,” but whether all its chapels together truly honor the one who is.

If Biola can recover the fullness of worship, both reverent and joyful, emotional and theologically rich, it may find that the most faithful act of worship is unity itself.

To remain faithful to its spiritual purpose, Biola must reclaim a higher vision of worship, one that reflects the weight of divine holiness and the humility of redeemed creation, while accounting for the denominational diversity of its students. Worship, regardless of the form, ought to be an act of holy reverence that upholds a tradition and sacredness, one that is both central to the history of the church and important for believers to be reminded of today. In considering the proper role and execution of worship, it is vital to ensure that students are being drawn beyond themselves, lifted from mere sentiment to holistic transformation, in which body, mind, and soul are wholly centered on God alone.