After 39 years of dedication to Biola’s art pedagogy, Dan Callis III, a professor of art, is retiring and transitioning to a full-time art practice.

The art department hosted a retirement party on April 23 with students, staff and professors sharing pivotal moments where Callis impacted their lives. The night continued with a commissioning prayer and ended with a video from colleagues and past students on Callis’ continued legacy. He was awarded the Faculty Emeritus award, granted by the president for full-time faculty who have taught for at least 10 years and demonstrated excellence in teaching and service.

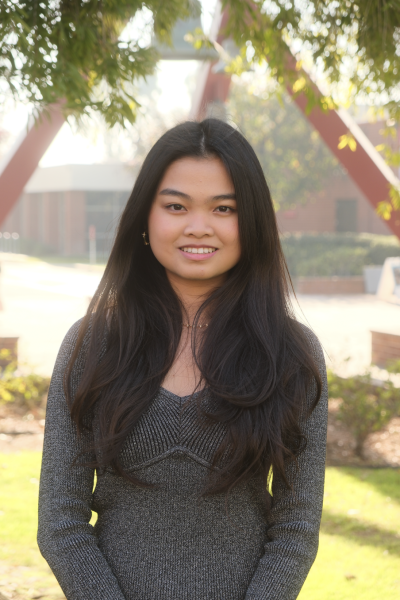

As an art student, my studio is situated right across his office, where I can see him engage with students almost all the time. When I went to interview him, Callis welcomed me to his office full of students’ and his own artwork and in a corner of his office is a corkboard that flashes a quote: “Give more than you take.”

Callis sees with the eyes of an artist when he hears the Psalms, parables, Christ calling the disciples or the Resurrection. He is filled with visual metaphors. A visual and poetic understanding of the world has always come most naturally to him. His theological imagination informs his artistic imagination and vice versa, visible in his life, family and community.

Callis has left and continues to leave an indelible mark on generations of students. Yet for those who know him, his greatest work isn’t only found in galleries — it’s also found in the lives he impacted through his praxis of gentleness and artistic imagination.

A LIFE SPOKEN INTO BEING

Callis grew up an hour southeast of Los Angeles. His maternal grandmother was the first person to spark his passion for art.

“She had a big garden and she turned a little enclosed porch into a [painting] studio,” said Callis. “[When I was] a little boy, she would take me out to the garden and have me help her plant, climb up the tree and pick the fruit out of her trees.”

Callis remembered rushing into her studio as a child, smelling the strong scent of turpentine and seeing her metal palette full of glistening oil paints. He would look up to her canvas that had a new scenery painted every time.

“She painted beautiful landscapes and the ocean, the mountains, river deltas, all places that were strange to me,” said Callis. “But they were like windows into a world.”

Callis’ father inherited a studio from his own father, who was a naval architect. Because of that, Callis saw his grandfather’s blueprints of steamer trunks with a navy aircraft carrier and designs of the Mark Twain riverboat in Disneyland.

“That’s when I started drawing as a little boy, to see boats, sailing boats and battleships and all,” said Callis. “I started drawing and I became the kid who drew things.”

He always had the appetite for art as it touches his soul with a kind of “romantic heights, so full of earnestness and angst.”

However, he wasn’t interested in art classes until high school, where he took ceramics for four years. Additionally, in college, he studied marine biology because he did not know that art could become a career. To him, it was just a domestic hobby exemplified by his grandfather and grandmother. But during his freshman year, he met a great art professor who posed art as something to be engaged seriously, augmenting Callis’ understanding of the arts.

“The art professor was so invested in the idea that art was a way to engage the world, language and ideas and that if you look at the history of any civilization, at the forefront of thought is art,” Callis said. “Art and philosophy and then science follow to make sense of what the artists and the philosophers are doing. So it suddenly turned into something really serious.”

SENT OUT BEYOND RECALL: A VOCATION

Callis became a Christian during the summer after high school, riding the wave of the Jesus Movement. That summer, he worked at a camp that was for moderately and severely intellectually disabled children and adults. There, he saw lives full of joy in the most unlikely places.

“I didn’t know these parables yet, but I was living amongst the least, the most broken, marginalized and they were full of life and joy, and they were free of the burdens that I felt like I was carrying. They felt wiser than I did,” he said.

He then recounted where the dots started to connect and he began to see the world as Jesus sees it.

“I felt [like] opening my heart up,” Callis said. “And then it seems that summer, when I was hanging out with my sisters, I started hearing parables about the last shall be first and the weak will be the inheritors of the Kingdom, all those metaphors made sense … something so paradoxical holds so much beauty and truth.”

Christianity gave him words for his experience of beauty amidst the unaesthetic.

“People weren’t physically beautiful, but their hearts and souls were beautiful. So [in] that sense, then in my conversion, this linking beauty to [the] Christian idea was so much more complex and profound than the Greek version of beauty as the ideal,” he said.

Seeing that he could interact with God and the world through art, he pursued and completed a Master of Fine Arts at Claremont Graduate School while continuing to serve the disabled community. Yet throughout that time, he felt intellectually and spiritually isolated in the art community and thus sought to teach at a faith-based institution.

“It’d be wonderful to be able to teach a young artist and just have [faith conversation] as part of the teaching from [the beginning] so they wouldn’t have to waste the time that I felt like I had to and have a sense of permission to respond to this calling,” Callis said.

Callis started as an adjunct professor at Biola in 1986 and was invited to come on full-time shortly after that.

A FLAME THAT LIT MANY LIGHTS

Callis’ commitment to faith as an artist has inspired other artists to understand their role in the world. Jonathan Puls, now the chair of the art department, was once a student in Callis’ class. Shortly after a Missions Conference, Callis noticed that Puls was wrestling.

Puls said, “The world is going to hell, and I’m sitting here drawing this trout fish.”

Callis honored that frustration and told him that “God wanted me to tell you he doesn’t need you right now. He wants you to learn how to make your work good so he can use it.” He continued, “And that was a word for me, too. What we do as artists, we have to do in silence, we have to draw where we work, but we work to give it away. So without this [silence], we can’t do that. So whatever those little voices are, they’re saying, you’re wasting time… service starts with preparation.”

Callis elaborated that the artists serve the community by first identifying the community they’re going to serve.

“Then I need to love and respect that community to make a thing that’s worthy of their attention. And if I’m not taking them seriously, then that seems disingenuous. I want to find a place where we share a language,” he said.

He advised students to take their academic practice seriously, shaped by the community they are serving or plan to serve.

“Slow down, my son, and just learn it first… [But] maybe now, you’re already on the mission field. You need to start perceiving yourself, if you haven’t yet, as a transitioning professional artist, [and this perception] is going to shape all the rest of your choices or decisions that you’re making,” he said. Our preparation is already a mission field, as we set our eyes on a service that is informing our choices today.

BEAUTY, TERROR AND ENDURANCE

Callis shared that his faculty peers, the art students and the community are what kept him all these years in Biola. He recognizes that the Biola art department is a unique place.

“It is, it has been and it continues to be, a place of challenge and encouragement. A place [that] expands a theological imagination. It’s a place that holds paradox and questioning. It’s a safe space for those kinds of aspirations. The faculty is deeply committed to the care and mentoring of the students. I could say that without hesitation for 39 years.”

John Coe, director of Institute for Spiritual Formation, responded to a spiritually challenging exhibition that one of Callis’ students produced.

“What you all in the art department are doing is profoundly important in terms of spiritual development, because you allow your students to wrestle with the dark night of the soul… the difference between what you and I do, is that we do it in the inner office, but you share it with community and that could be frightening for so many people,” Coe said.

This, for Callis, is part of what artists are called to: create a work to give it away to the community that creates a space for communal engagement; whether that be an encouragement or a wrestling. His role as a professor was to allow students to wrestle through their questions. Because the world, with its pleasures and pains, is an absurd thing to get hold of.

Callis recognizes its grandiosity, antiquity and complexity, “I’ve always seen the world as a place of wonder and curiosity, constantly unfolding. I see human beings as delightful, complicated, doing the worst and best to each other. And we have a God who keeps speaking of wonder and love, and keeps coming to us in spite of what we do.”

GIVE ME YOUR HAND

The legacy Callis hopes to leave behind lies in people and a courageous pursuit of the arts.

“The legacy is the students, and [I want to leave behind] a serious and joyful curiosity, fearless in the face of culture, because you’re trying to do something that’s so much bigger.”

For him, retirement means an end to another beginning.

“I have spent part of my days for the last 39 years trying to encourage young artists to make a thing. I’m going to now use that time and energy to make more things and make new things,” he said.

A final piece of wisdom from Callis to art students as he transitions to full-time art practice is to “keep being curious, keep being generous, and keep being courageous. Remember what you are doing is absurd and so very, very important. Also, don’t forget to brush your teeth and put on deodorant.”

He inspired many with his spirit of gentleness and generosity to guide young artists, mentoring them in a pivotal, transitional time to professional vocation. In the times when students wonder if their faith stands the questions of life, Callis held their hands and walked with them out of the night.

This is Callis’ most treasured poem, “Go to the Limits of Your Longings,” by Rainer Maria Rilke. A poem that is not only close to his heart, but one he has lived out.

“God speaks to each of us as he makes us,

then walks with us silently out of the night.

These are the words we dimly hear:

You, sent out beyond your recall,

go to the limits of your longing.

Embody me.

Flare up like a flame

and make big shadows I can move in.

Let everything happen to you: beauty and terror.

Just keep going. No feeling is final.

Don’t let yourself lose me.

Nearby is the country they call life.

You will know it by its seriousness.

Give me your hand.”