The rise of Large Language Models (LLMs) has significantly impacted the job market and education. LLM is a program that is trained on a massive dataset of various forms of written language to learn patterns that enable it to generate text, known as Natural Language Processing (NLP).

Schools, corporations, students and faculty are now having to navigate and adapt to this technology. Biola launched its new artificial intelligence (AI) Lab and AI Venture Studio on Sept. 12, 2024, an initiative the university is adapting to be a leading voice in the field of Christian ethics and technology. They also recently hired an AI expert in the School of Science, Technology, and Health (SSTH) who’ll propel this initiative even further.

The AI Lab faculty leadership is composed of faculty from various schools, primarily science, technology, engineering, mathematics (STEM) and business. Michael Arena, former Amazon vice president and current dean of the Crowell School of Business, is spearheading the initiative alongside Stefan Jungmichel, a recent graduate (master’s) of the business school. David Bourgeois, associate dean of Crowell, also serves as the director of the AI Lab.

STEM and business aren’t the only fields significantly impacted by the rise of LLMs. As LLMs primarily operate through language, it has significantly impacted the field of humanities. I went on to interview three English professors to discuss how this innovation has influenced their field and teaching approaches.

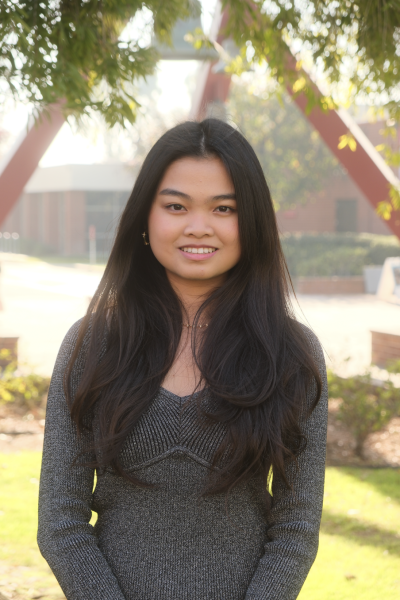

Bethany Williamson is an associate professor in the English department and has been teaching at Biola since 2015. Her PhD research focused on 17th & 18th-century British literature and she taught classes such as “Topics in Diverse Lit” Core courses on stories from the Middle East, robots and AI and global retellings of “Pride and Prejudice.”

Christine Watson is an assistant professor in the English department and has been at Biola since 2007. She has taught core writing courses since 2014 and is the co-director of the English Writing Program: a two-course sequence which includes the first-year and third-year composition courses.

Aaron Kleist is a professor of English and started his career as English professor 30 years ago. He completed two doctorates at Cambridge in Old English literature and taught there for a time before coming to Biola in 2001. He teaches classes such as Introduction to Critical Thinking and Writing, or English 313, Dystopian Literature and Technical and Digital Writing.

WHAT ARE YOUR THOUGHTS ON THE RISE OF GENERATIVE AI TOOLS, SUCH AS CHATGPT, AND THEIR IMPACT ON WRITING AND EDUCATION?

Williamson: Our tech tools have evolved much more quickly than our ethical reflections on and framework for when, why, and how we use them. For instance, generative AI had already scraped the web for copyrighted materials before authors realized that their work was appropriated without permission or compensation. Meanwhile, as AI tools make writing more efficient, with made-to-order templates of genre/tone, we’re seeing administrators outsource condolence emails, students outsource those five-paragraph essays, and professors using AI to grade those student papers. When machines are grading machines, one should ask: what have we lost?

Watson: There is a lot of fear out there about what could happen with generative AI and how it might impact our world, our jobs, our humanity. To be sure, I think our communal responsibility cannot be underestimated here. We need to make sure to think with each other about ethical choices and policies. But, in terms of my specific thoughts about the students in front of me today? My biggest concern is whether they perceive their own minds as so uniquely superior to the thing that we call generative AI. I don’t want students to underestimate their God-given abilities to create and make distinctly human choices. I’m less concerned about “busting” students for plagiarizing, and more concerned about a worldview that offloads things that make us distinctly human and does not defend against corporate creep.

Kleist: I think it’s great, neutral and alarming all at once, great in the sense that I’m an early adopter, I’m a technologist and a futurist. I like seeing what human beings bring to the table in terms of new technology. I find it absolutely astonishing that the Lord, looking at the Tower of Babel, would say that if human beings worked as a unit, speaking the same language, and they’ve begun to do this, nothing they plan to do will be impossible for them. That’s an astonishing thing for the living Lord of the universe to say. On the other hand, it’s also a neutral tool. Pragmatically, I want my students to have the mental capacity, skills and tools, to do robust analysis on their own, to write from scratch on their own, to have that capacity and also recognize that increasingly AI is being infused into the working world in a number of ways, whether it’s from something as simple as Grammarly. Where a whole society is being influenced by a single corporation as to style and how to write. Well, that’s not a small thing and all the way to the use of generative AI to reduce content of various sorts that has one’s name on it.

HAVE YOU NOTICED ANY CHANGES IN STUDENTS’ WRITING QUALITY OR STYLE SINCE THE INTRODUCTION OF THESE AI TOOLS?

Watson: All right, to answer this question, let’s start with theology, shall we? We know that people are fallen and sinful, that as humans left to our own devices, we are prone to take shortcuts and settle for mediocrity. We know that, if we are not abiding in God, we drift away from God and not toward him. This is true for all believers. But we also know that we are being shaped and sanctified every day by the work of the Spirit, and those who live in Christ want to be conformed into his likeness. The short answer here is that a lot has changed in the world lately (including generative AI and LLMs), and Biola students continue to impress me. By and large, I think Biola students want to use the tools available to them in ethical, appropriate ways, but sometimes it’s unclear how to go about it. The world of AI can feel like the wild west, and sometimes students haven’t thought through all the implications of what is available to them. So, yes; I sometimes see weird, manufactured, robotic-type AI stuff in student writing, and I acknowledge that we all can tend to make uninformed and often sinful choices. But at the heart of the typical Biola student, I usually sense a desire to be transformed into his likeness and an openness to being shepherded through the process.

Kleist: It may be too early to tell. It’s a good question and I can see the inevitability of the influence of such tools as Grammarly on the tone and style of written communication for nations. I think it’s going to be subtle for a long time. It used to be that English professors could tell pretty obviously when somebody had used the word thesaurus to introduce highfalutin terms when that really didn’t fit the context. In the early days of

ChatGPT, for example, if a student has been writing at a certain level and all of a sudden the style changes, those things could be obvious. But right now, you’ve got tools that can take the output of generative AI LLM and rewrite it, pitching the academic level higher or lower depending on the context, run it through plagiarism checks and output something that’s completely original, and then you’ve got AI bots that are designed to detect that. It’s a cycle. So one issue that’s certainly worth discussing is, as teachers, what do we do about it?

HOW HAVE YOU SEEN THE FIELD OF TEACHING WRITING EVOLVE OVER THE YEARS?

Williamson: It seems that AI tools like Grammarly and ChatGPT have become to writing what the calculator is to math or Google Maps to driving: just like I don’t trust my ability to navigate LA roads without my phone, I see students second-guessing not just their grammar but also the very ideas they’re trying to express. I notice students self-sorting into two general categories. On one hand are those who are more interested in a grade and degree than in the actual challenge of learning; they tend to justify shortcuts — including AI-generated prose — that help them complete assignments faster. On the other hand are the students who embrace the writing process as a way to figure out precisely what they’re thinking and how they can communicate it clearly and compellingly. Writing doesn’t necessarily come easily to these students, but as they work on it — persisting through brainstorming dead-ends, outlining their argument, crafting and editing sentences — they also demonstrate sharper, more nuanced thinking, too.

Watson: In my time teaching writing, a lot has remained consistent in the field: writing programs seek to help students see writing as both a way to present an end-product (such as a research paper) as well as a way to work out our thinking (such as a reflection on a reading). The field of writing studies values writing as an iterative process where teachers give feedback at multiple stages, and students revise their work. We see the act of writing as a whole-person endeavor involving not just knowledge of language but affections, fears, even spiritual components. So, those in the field will often say they aren’t aiming for better pieces of writing, they are aiming to make students into better writers.

Maybe the thing that has changed the most over the years has to do with our understanding of higher education in general, and the way that view trickles into the disciplines. I’ve witnessed (in some spaces) something of a cultural re-framing of education away from a thing that nurtures our civic duty, helps shape character, and serves the common good. Rather, there is more talk about education as a means to an end and a return on investment (ROI). More and more, you hear people talk about getting classes “out of the way” as if those classes had little benefit to the overall educational experience. In some ways, the danger of viewing education solely as an economic transaction overlaps with viewing writing as solely a presentation of data. Although ROI and data presentation are important, there’s much more to the human experience of education, and there’s more to the human expression of writing.

Kleist: Human nature remains the same; technology, circumstances, pressures, cultural pressures may change. But the human experience, human challenges, our role as Christians, Christian citizens, Christian intellectuals and professionals, that’s constant. So there are principles that are applicable to human beings down through space and time. That’s encouraging. It means you don’t have to always reinvent the wheel. There have been, however, some significant changes that technology has brought, obviously, and that the socio-economic realities of. Higher education has brought about. So as regards the latter, college is expensive. College has gotten more expensive. It is increasingly difficult for parents to justify students to justify becoming a philosophy, English, or history major when they have deep-seated fears that those majors will not result in jobs. Even though humanities, for example, train students in fundamental skills that employers have sought after for decades such as critical thinking, problem-solving, analysis, oral and written communication, teamwork, leadership, etc., in terms of writing, there has been an increased pressure to justify what we teach based on the applicability of course material to the workplace.

HOW ARE YOU INCORPORATING OR ADDRESSING GENERATIVE AI IN YOUR WRITING CURRICULUM?

Watson: The benefit of a Biola Core (GE) education – a thing that is different from other places – is the individualized, focused attention students get from their instructors, especially in writing classes. Generative AI may be fairly new to the field, but the temptation for students to cut corners in their work when they are stressed out, overwhelmed or when they don’t see the point has always been an issue. So, I address the use of generative AI along with other ways that we tend to resist the challenge of slow, methodical, process-based writing. In many ways, writing classes at Biola are run “old school” style, where you submit your work for feedback all along the way: brainstorming, outlining, drafting and so forth. Checking the process has always been part of the curriculum because the process matters a lot. And this is the benefit of the Biola Core education: students get individualized and focused attention from faculty. So in many ways, the existence of generative AI in new forms such as ChatGPT doesn’t change how we do business; writing is slow, messy, thoughtful and iterative. That said, some faculty purposefully introduce generative AI as a tool (that is limited!) and help students know when and how to use it, and I can see a place for that.

Kleist: I have colleagues in my department who would rather teach writing courses with no AI use whatsoever, and I deeply respect them for this. They are focused, for example, on the definition of what it means to be human and the cultivation of the human mind and character. I take a different approach. I spent all semester — and most of the semester before — using a lot of those tools and spending that time teaching students to recognize precise, logically clear, tight, evidence-based argumentation and point out weaknesses of LLM. I also say pragmatically, this is the world in which you’re entering. AI is increasingly going to be requisite for your success in both the professional and personal arena. I want our students to be able to say, “For the problem you mentioned, here are tools that you could use. Here are some of the limitations of them, and here is how I would go about using this combination of tools in an iterative fashion to produce refined results.” Use AI tools and

identify what words you drew from them and cite the source and the prompts that you used, what was the process to get there? If you’re able to do that, fantastic. That means that you have thought through the process, you didn’t just take the first thing that it said; it means that you practiced citing your sources, which is important for helping others gain confidence in you.

HOW CAN STUDENTS BEST PREPARE THEMSELVES?

Williamson: It’s easy to learn how to use a tool like ChatGPT; it’s harder to discern when and why to use it, and how to add your own human value to a given project or conversation. Students — and workers — who have cultivated skills of thinking carefully, critically, and creatively, with discernment and attentiveness, will stand out from others who can only think according to algorithms or influencers. When deciding whether or not to use GenAI on a particular assignment, ask yourself: what problem am I trying to solve, by using this tool? If you’re trying to avoid the hard work of critical thinking and clear writing (hint: if your professor tells you not to use it!) then think again: the purpose of earning a liberal arts degree is to train and develop your mind and character, and there is no shortcut to that end.

Watson: I can’t count the number of times I’ve heard graduation speakers say something like “bet on yourself!” This is, of course, pretty good advice if the hearer is doing the work to make themselves a “good bet.” When it comes to writing, I would advise students to bet on their own minds over the algorithms of a machine. That does take work, but that’s why we are here at the Biola: to cultivate a posture of learning and growing and getting better and better at the things we hold dear. And when it comes to an ethic of commitment, Biola students do not disappoint. I’d bet on a Biola student all day long.

Kleist: One, be good Christians; and two, play. Here’s what I mean. First, I want students to be really thoughtful, intentional, and conscientious about the person they want to be. Ultimately, that means being shaped by the word of God and prayer and the community of the faithful to be more and more Christlike. That also means having integrity and taking ownership and responsibility for one’s choices and having really high standards for the character one has. Jesus defines, models and shows us a view of personhood that is radically higher and different than what the world offers, which says pursue your pleasures. [We are] to be robustly the blood-bought men and women of God, that for whom Jesus died, that’s a high call.

Once they’ve done that, then play, just try things out. Be ever curious. There are new tools being added every second to the array of technology out there. Have a plasticity of mind. That, I think, will do more for your ability to be flexible, adaptive and responsive.

DO YOU HAVE ANY MORE COMMENTS FOR STUDENTS OR EDUCATORS?

Kleist: Christians have always faced changing cultures, new technologies, and challenges that come from change. But our anchor, our foundation, our tower is constant. It may seem unglamorous, it may seem trivial, but the fact is that as the world changes around us, the wind and the waves of new technology or other factors are simply too big for us. Students and older adults are tempted to be afraid because of the unknown future and the choices that they must make. The call of Christ to the Christian remains the same. Every day, read the word and earnestly seek him in prayer. Put first and foremost his kingdom and righteousness and he will take care of everything. If we look at ourselves, we are afraid because we know we are so small. If we fill our eyes with the living Lord of heaven and earth, everything else gets put in perspective. Whatever technology we are called to master, the world changes and its demands grow greater, we know that the greatness of the Lord’s goodness, power and love are more than enough for us to flourish and fly.