(This story was originally published in print on Feb. 14, 2019).

On Jan. 19, a Twitter account called “Talia” posted a video that allegedly showed an altercation between students from Covington Catholic High School and an elderly Native American man in front of the Lincoln Memorial. The video was viewed over 2.5 million times and it seemed like almost everyone who saw it was outraged.

Suddenly, the narrative collapsed. Longer and more detailed videos emerged that showed the full context of the incident. It was soon discovered that network bots were behind the proliferation of the video, and, recognizing the “fake and misleading” nature of the message, Twitter suspended the user who originally shared it.

The embarrassing situation gave the click-happy media a temporary black eye. The most foolish of pundits immediately condemned the boys, the slightly less foolish defended them and the least foolish observers waited for more information. The wisest commentators of all, however, were asking one question: Who the devil cares?

MASS-PRODUCED VIRTUE

Let me be perfectly clear. If a group of disrespectful students were genuinely harassing an elderly man who was just trying to finish a song, those students should be punished. Such students should not, however, have their faces and names splattered across social media to make them a byword among the nations. They should not have celebrities calling for them to be doxed and exposing them to death threats and humiliation. Some people, especially children, do not live public lives and some stories simply require no reaction from the broader public.

If one is willing to dig far enough into one’s memory, a million tiny, infuriating stories will be resurrected to life like zombies, giving us a faint reminder of the righteous indignation we felt at the time.

One remembers the controversial 2017 United Airlines removal of David Dao, the frequently memed shooting of Harambe the Gorilla and the distasteful photo showing so-called comedian Kathy Griffin holding up a prop made to look like the bloody head of President Donald Trump. None of these stories had any tangible impact on our lives. While some of these stories included actual injustices, no laws were broken. The fact that these infuriating stories could not be brought before a court of law somehow meant that they had to be brought into the television sets and Facebook feeds of three hundred million Americans.

There is only one reason why we gobble up 45-second cellphone videos and the dubious testimonies of random civilians. There is only one reason why such stories light a fire of rage and indignation in our hearts. Indignation makes us feel virtuous. Human beings are conditioned to feel good when we stand up for a virtuous cause, when we defend the innocent and batter down the proud. The fact that half the country piled onto a group of high school kids without bothering to explore the context of the situation is part and parcel of this defect in all of our thinking.

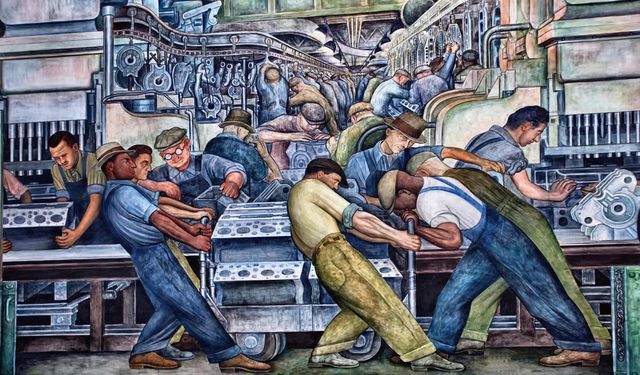

THE MORAL ASSEMBLY LINE

Just like everything in this culture of ours, our virtue is mass-produced. Every detail of every message from toothpaste commercials, to blockbuster movies, to this very article is placed with the intention of keeping the consumer listening, watching and reading. News and social media are no different. Henry Ford pioneered the assembly line method over one hundred years ago. Today major news outlets continue his legacy by churning out story after story with the efficiency and moral conscience of a sweatshop.

Indignation alone does not make a person virtuous. A person’s participation in the outrage mills pushed on them by Facebook’s algorithm does not grant that person moral superiority. Why must it be the ritual of every well-meaning internetite to comment on and denounce every hot take they read, as if they were genuflecting to the invisible gods of moral connectedness? It is almost as if we feel as though if we do not denounce the controversy immediately, we will somehow become complicit in it.

Just because we are more connected than ever does not mean we have the duty to denounce every unkindness that some bystander is able to upload to Twitter. We should not climb on top of the slain bodies of moral outcasts and internet pariahs just to look down on other people or look to whirring gadgets and packed stadiums for things we can discover by a babbling brook with a pensive mind. We should reject the mass-produced morality of our age. The kingdom of God is within us, not on Twitter.