While researchers at Pew Research center have recently claimed the number of black Americans imprisoned has declined substantially within America, almost by 25 percent since 2009, a general fear seems to exist in prison systems when the term “New Jim Crow” is used.

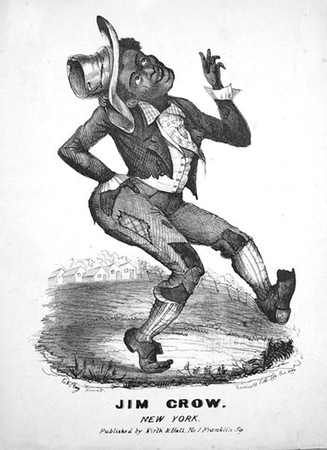

PRISONS BANNING BOOKS

Particularly, within America’s penitentiary communities, there has been a lot of dissention over the book on mass incarceration by Michelle Alexander, a civil rights lawyer and previous clerk of the Supreme Court—“The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in an Age of Colorblindness,” and weather it should be available for reading by those incarcerated. The book draws parallels between the Jim Crow laws—the Webster dictionary defines Jim Crow as “ethnic discrimination especially against blacks by legal enforcement or traditional sanctions”— and the current prison and judicial systems in America.

According to the New York Times, as of Jan, multiple prisons within the United States have banned the reading and possession of Alexander’s bookbecause of its likeliness to “provoke confrontation between racial groups.” In response, Alexander shared the ban on the books and the inmate’s access of them was not an accident, but predictably intentional.

The question provoked by all this information lies in this: what does this mean for our country’s judicial and prison systems? For some, it comes as a glass-shattering awakening to the truths of the corruption of our government, yet for minority members of our country this seems to provoke a reaction similar to Alexander’s herself—sadness that runs deep with the proven fact: there has been and always will be a ‘new’ Jim Crow.

However, there is hope. Just this month, New Jersey was forced to remove its ban placed on the book because of a claim that its removal from state prisons was an “ironic, misguided and harmful” instance of censorship.

EDUCATE WITH TRUTH

Although this does not free the wrongfully convicted, there is hope that with the knowledge of the passion those incarcerated possess for education on the truth, there will come about a change in the prisons. On their discussion of Alexander’s book, Campaign to End the Death Penalty states:

“Anti-racist arguments that were once considered too aggressive have now broken into mainstream political consciousness mainly because the facts have become so impossible to ignore.”

While this is good news for activists, it remains safe to argue that the number of those enraged by the unfair and serious nature of this conversation is still too minute. Perhaps the gradual forcing of the prison’s hand will eventually cause blind eyes to see the truth, but we must pray for a bigger change. Our judicial systems are biased, they are racist, and although the unbanning of a book is a step, it is not nearly enough.