Two hundred people Friday night and 140 Saturday morning assembled in Mayers Auditorium to acknowledge the impact of Francis Schaeffer’s life and teachings on today’s culture.

Schaeffer, considered among the great thinkers of the 20th century, argued that Biblical Christianity gives sufficient answers to the big questions in life, but the only answers that are both self-consistent and livable,” according to The Shelter, a Francis Schaeffer Web site.

Speakers at the event said Schaeffer is possibly more relevant now than during his life, and can be consulted for answers to modern issues like global warming and the war in Iraq.

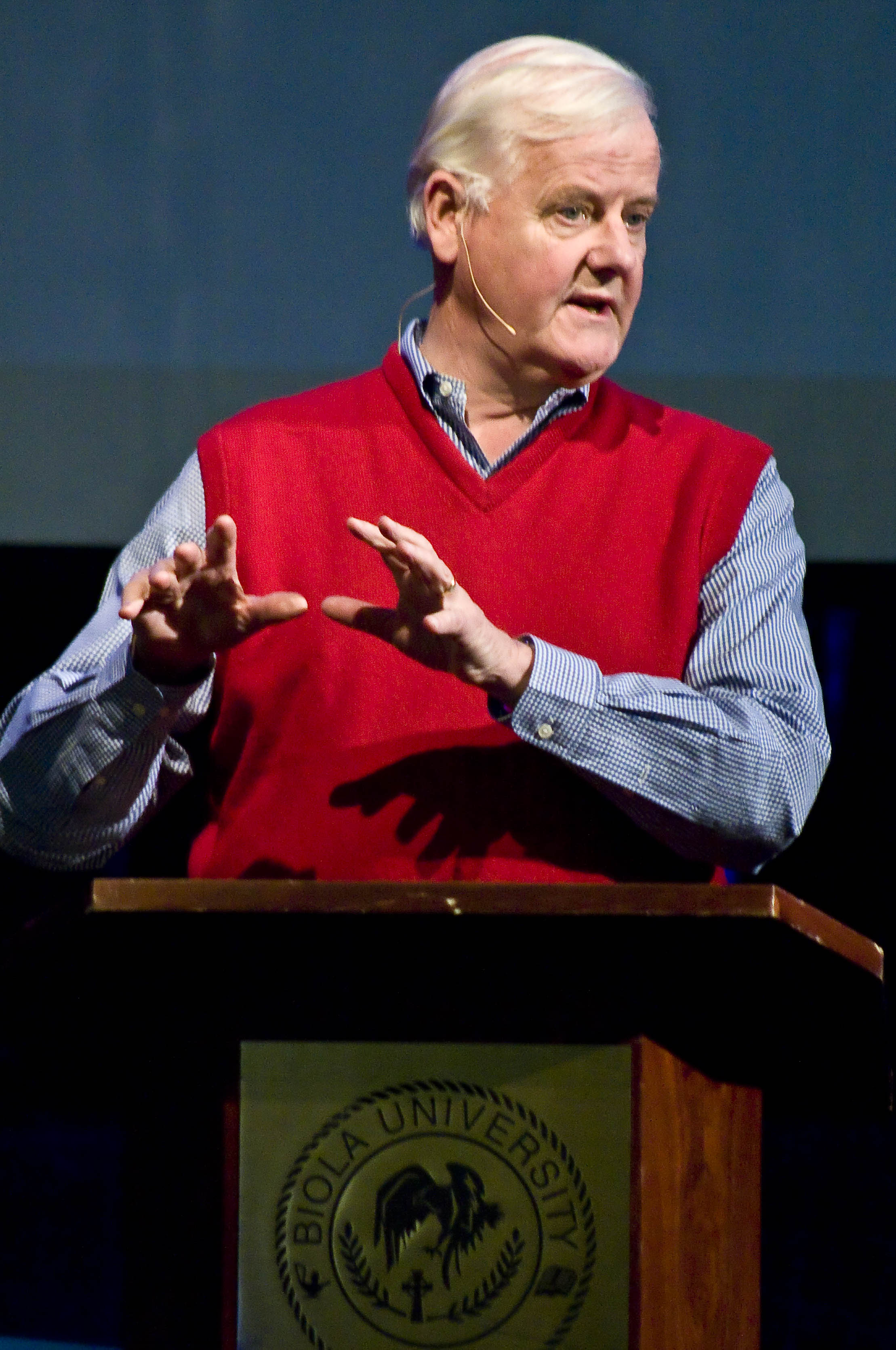

Speakers included Ranald Macaulay, speaker and author who worked with Schaeffer and L’Abri. Os Guinness, founder of Trinity Forum, a group that holds seminars addressing modern issues in the context of religion and philosophy, and Fred Sanders, a professor in the Torrey Honors Institute.

Francis Schaeffer’s work became prominent in the 1950s and continued throughout the early 1980s. He founded L’Abri, a conversational learning center for European students in Switzerland, calling them into a “true spirituality” through the growth of faith and reason. L’Abri schools have now been founded in 11 countries, and emphasize integration of studies in philosophy, spirituality and lifestyle, according to the school’s Web site.

Os Guinness, son-in-law and student of Schaeffer’s said that today’s economic challenge is the first “made in America” problem. He focused on the founders of the country who held the “audacious idea of freedom” close to their hearts by winning, ordering and maintaining it through their actions.

Worldviews of Americans have shifted since the time of the founders, as Americans create a privatized and irrelevant faith, Guinness said. Today’s change must come, not from technology, but from the application of fundamentals, he said. He added that today’s Christian leaders must look to Schaeffer’s example of a conversational yet radical way of life.

Ranald Macaulay underscored the relevance of Schaeffer’s teaching by expounding on his “prophecies” of future pressures like terrorism and the disparity of rich and poor, all of which have come upon America today to threaten the founding freedom of this country. The West will either return to the absolutes it is founded on, or will collapse at the center.

One of the “crippling deficiencies” of the West today, Macaulay said, is the virus of technique, or misuse of technology, traced back to the Industrial Revolution. Americans tend to believe that the making of more machines will create a better society and that technological programs answer life’s problems, he said. He argued that Christianity should be providing a person, namely Jesus, to answer life’s problems, not a program.

How does a Christian present a person? McCauley proposed that the Church needs the countercultural spirituality that Schaeffer exemplified. Christians must prioritize character, not comfort; community, not commuting; confrontation of ideas, not compromise.

Macaulay challenged Christians in America to quickly revive authentic spirituality, as many of his fellow European Christians are being openly persecuted. The failure of technology to fill the void of “de-Christianization” can be seen in his country already: Europe’s use of cellular phones has reached 90 percent, according to European Mobile Statistics, yet its Christians are treated with incivility and hate.

“Schaeffer’s warnings are more ominous and threatening today,” Macaulay said, “Things he saw coming are here, uncomfortable as they may be.”