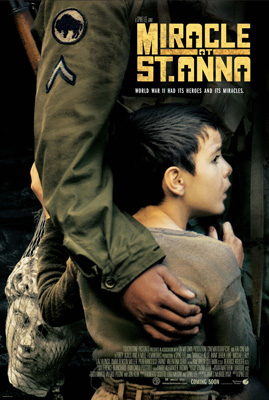

Perhaps you are already aware of the conflict that led to the creation of “Miracle at St. Anna,” Spike Lee’s new World War II film, but if you aren’t, I’ll recap the event for you. After Clint Eastwood released “Letters from Iwo Jima” and “Flags of Our Fathers,” Lee berated him for the lack of black characters in either film. Eastwood responded by informing Lee that he should “shut his face.” Instead of giving a similarly witty retort, Lee made “Miracle at St. Anna,” a film about the trials of four black soldiers who are trapped in a Tuscan village by the German army. My fear going into the theater was that the animosity between the two directors would cause the movie to be a cobbled-together hack job created only for the twin purposes of putting black people into a World War II setting and smacking Eastwood in the face.

The good news is that there are better intentions behind “Miracle at St. Anna.” Lee really does seem to care about the story he is telling, and it is one with the potential to be unique and thought-provoking. The strength of the film lies in effective individual scenes; there is a devastating one in which Nazis rain bullets on the troops while “Axis Sally,” a honey-tongued Nazi propaganda broadcaster, taunts the advancing Americans with the promise of a freer life in Germany. However, the movie suffers one mortal wound: the plot lacks focus.

Meandering as it is, the plot revolves around four buffalo soldiers on the front lines during the second world war. Stamps, (Derek Luke) the leader of the group, is passionate about fighting for his country and his people. With him are Bishop (Michael Ealy), Negron (Laz Alonso) and Train (Omar Benson Miller). After the Axis Sally firefight, the four find themselves stranded in enemy-occupied territory and stumble upon a village which is sympathetic to the allied cause. Once they have crossed the river, however, the audience is hit with a torrent of tangents and never recovers. Several subplots vie for prominence throughout and a few sub-subplots are even introduced, none of which are resolved. Each character has a plotline of their own, but not of the revealing, Freudian variety which might have added some depth to the characters. There is a subplot involving one of the characters as an old man that adds little to the story, and another that presents for the audience an artifact with tantalizing potential for meaning and symbolism, but instead loses any relevance in the wash of storylines that engulf the film. By the time I left the theater, I was not sure what the point of the movie was, because there is no definable, main plotline.

“Miracle at St. Anna” aspires to be as epic and powerful as “Saving Private Ryan,” but in the stretch to achieve epic status it loses its way, and we are left as dazed and confused as the plot.