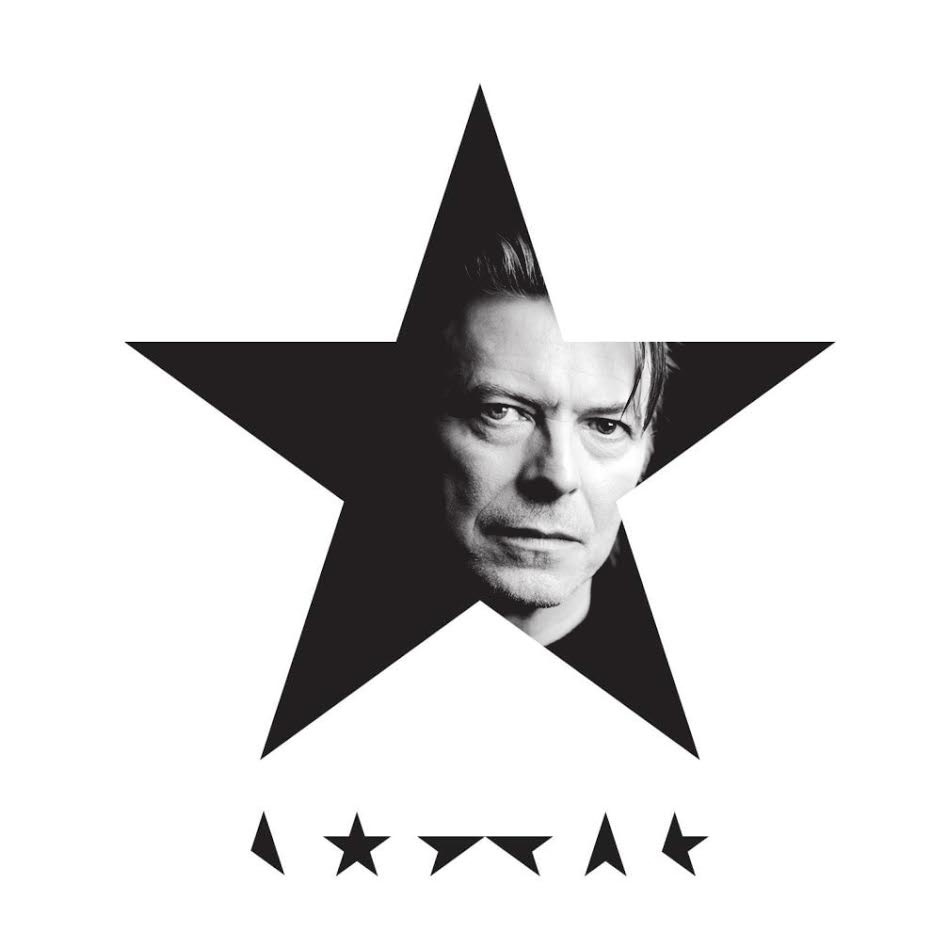

The moment I heard the news, I got up and put my copy of “Scary Monsters (and Super Creeps)” on my turntable, carefully placing the needle over the fourth track on side one. “Ashes to Ashes” spun, and the world collectively felt the weight of this crushing loss. We truly lost a hero, and he left this world with one last goodbye, his twenty-fifth and final album “Blackstar.”

Simply immortal

As a lifetime David Bowie fan, one of the hardest parts of his death was how I initially took “Blackstar” for granted. Many of us felt he was simply immortal. Free from any of the entrapments of this earth, he existed in the far reaches of space, beaming us album after album of genre-bending masterpiece. What still gets at me is that when Bowie released “Blackstar” on his 69th birthday, Jan. 8, 2016, I shelved it among the other new records I was in the midst of listening to. I thought I would just get around to it. No part of me considered this was his goodbye, his way of leaving this world with one more statement — one more reflection.

Two days later, I was crying in my room, listening to all of the Bowie vinyl in my collection. Everything made sense at once. What we all thought was just typical Bowie weirdness in the music video for “Lazarus,” was a carefully constructed biography of his losing battle with cancer. “Look up here, I’m in heaven / I’ve got scars that can’t be seen.” The title track saw Bowie repeating the lines “I’m a blackstar,” which later came out to be a medical term for a type of cancerous lesion. Bowie kept his battle with cancer private, and left this world from a metaphorical stage. He was always up to something, crafting his image and sound even in the weeks leading up to his own death. He knew what was coming, and made undeniably brilliant art as a result.

Invigorated and inspired

Also in typical Bowie fashion, he went out invigorated and inspired. “Blackstar” is as progressive as we can expect from a record inspired by Kendrick Lamar and Death Grips. These influences come through in a striking way, from the nearly violent guitar work on “Sue (Or in a Season of Crime)” to the jazz instrumentation that creates the somber atmosphere of “Lazarus.” Bowie was always an advocate for persons of color, even going on MTV and criticizing them for not playing enough music from black artists. He was an advocate for anyone on the margins, from persons of color to LGBTQ members of society. “Blackstar” highlights the sort of diversity he was known for bringing in his life, and now he has carried it with him into death.

A few weeks after his death, my friends and I met up at a Bowie tribute night in L.A., surrounded by fellow fans with tearstained lightning bolts painted on their faces. The DJs played several of the deep cuts from Bowie’s career, but when “A New Career in a New Town” from his highly experimental and widely praised “Low,” I felt a visceral pang of sadness. On the final track of “Blackstar,” Bowie samples this track, interjecting the haunting harmonica on top of the line “I can’t give everything away.”

Aftershock

My best friend and Biola alum Mack Hayden felt the same pang of sadness, and he texted me this later that night.

“I was feeling as emotional as you during ‘A New Career in a New Town.’ That’s one of the first songs I played after I heard the news. The title of that song is the best way I can describe what I hope happened for Bowie after his death.”

I hope so too.