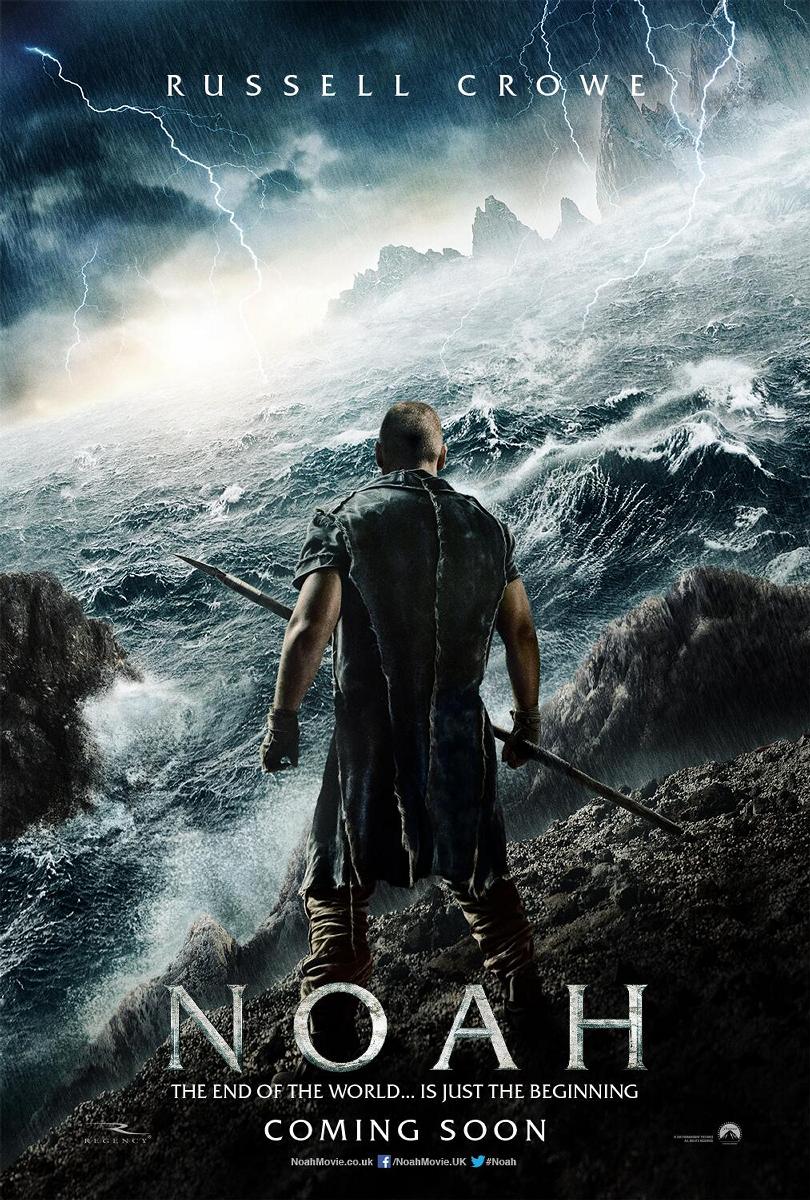

If you’re expecting Noah in flowing robes with a woolly white beard, ushering animals into an ark two-by-two, “Noah” will shock. Here, grit and pathos splatter the Genesis seafarer. “Black Swan” director Darren Aronofsky has been brewing this story since his teens. Finally, with co-writer Ari Handel, Aronofsky unleashes his imaginative retelling.

ARONOFSKY'S MYTHOLOGICAL RETELLING

The story is familiar, but Aronofsky’s plot blooms. There’s Noah (Russell Crowe), a man of the soil, his wife, Naameh (Jennifer Connelly), and their three boys. Toss in their adopted, but barren, daughter Ila (Emma Watson), and you have the family. They’re vegetarians, revering those creatures unmarred by the fall — the innocents, or the animals. After the creator sends visions — each artfully rendered — Noah builds, hoping to save the innocents from the deluge.

Other men, wary of the creator’s intentions, led by their king and Noah’s nemesis, Tubal-cain (Ray Winstone), want in on the boat. When Noah refuses, they plot destruction. To them, dominion over the earth is taking what you can, leaving behind waste and ruin.

Aronofsky is not basing the movie off some childhood recollection. The movie effuses painstaking research with consideration to all sorts of popular interpretations. The text is stretched and filled with fanciful ingenuity and a spiritual core.

This is a mythological retelling. The post-fall, antediluvian realm is thick with enchantment. Stars appear in the day sky, unfamiliar animals roam and glowing snakeskins pass on generational blessings. Noah’s grandfather, Methuselah (Anthony Hopkins), embodies this old world with his shaman-like healings and mountaintop wisdom. From a desolate ground, a revitalized Eden springs up, providing Noah with wood. This world is magical — you could also call it miraculous.

The flood hits and the movie shifts tones. It becomes a psychological drama. Echoing screams from the dying reach into the boat to haunt, and Noah listens. Like a Gustavé Dore etching of Dante’s “Inferno,” survivors clamor up a mountain before a wave brushes them aside. What great injustice the flood receives in our children’s Bibles.

NOAH WRESTLES WITH HUMAN SIN

Noah’s grasp of sin is the best I’ve seen in a movie. He understands all humans deserve death, even his family. His stalwart quest to see the creator’s extinction completed splits his family apart. Brutal emotions and desperate pain rock the second half.

While the second half rages like a Aronofsky picture, complete with visceral and cerebral stress, the first half is weak. There is intention with the tonal shift, but the first part feels Hollywood-ized with flat, archetypal characters. It’s made all the more stale by the post-flood story’s complexity.

The Watchers are most surprising. Taken from the “The Book of Enoch,” they’re not nephilim but fallen angels, encrusted by earth after disobeying the creator. Their addition nuances insights like divine assistance. But they’re also distracting sometimes, and used for out-of-place slapstick humor.

MOVIE DOESN'T FOLLOW RELIGIOUS RULES

The biggest flaw is Tubal-cain — an antagonist for an antagonist’s sake, only there to show what Noah is not. He could’ve been removed or cut back, but his insistent focus subverts a more pregnant character study of Noah and his family’s emotional turmoil.

Matthew Libatique’s photography and tech-wizards construct a truly epic scope. Long has it been since the Bible has become quality, cinematic art. It gives space to emotional experiences and is thought provoking enough to generate good conversation.

To say one should or should not see this movie for religious reasons is making “Noah” into something it never tried to be. This is a Bible story, with Aronofsky’s emphasis on “story.” His imagination was captured by something in Genesis he wanted to share with us. But like a great story, there are moments of deplorable, human brokenness and profound, unanswerable grace.