“The Lord of the Rings” movie trilogy is not only hailed as a piece of striking cinematography and a great credit to the name Peter Jackson — but as chock-full of Christian themes and a great work of art. Yet I wonder: Would Christians adore “The Lord of the Rings” had it portrayed a more accurate depiction of wartime violence?

While Jackson was not afraid of a nice beheading, the films are actually quite tame with regard to violence compared to other war movies. Aragorn’s flashing blade is silver, not red. This is not to say the films should have been bloodier; but had they been so, they would have been no less a testament to the work of their openly Christian author, J.R.R. Tolkien.

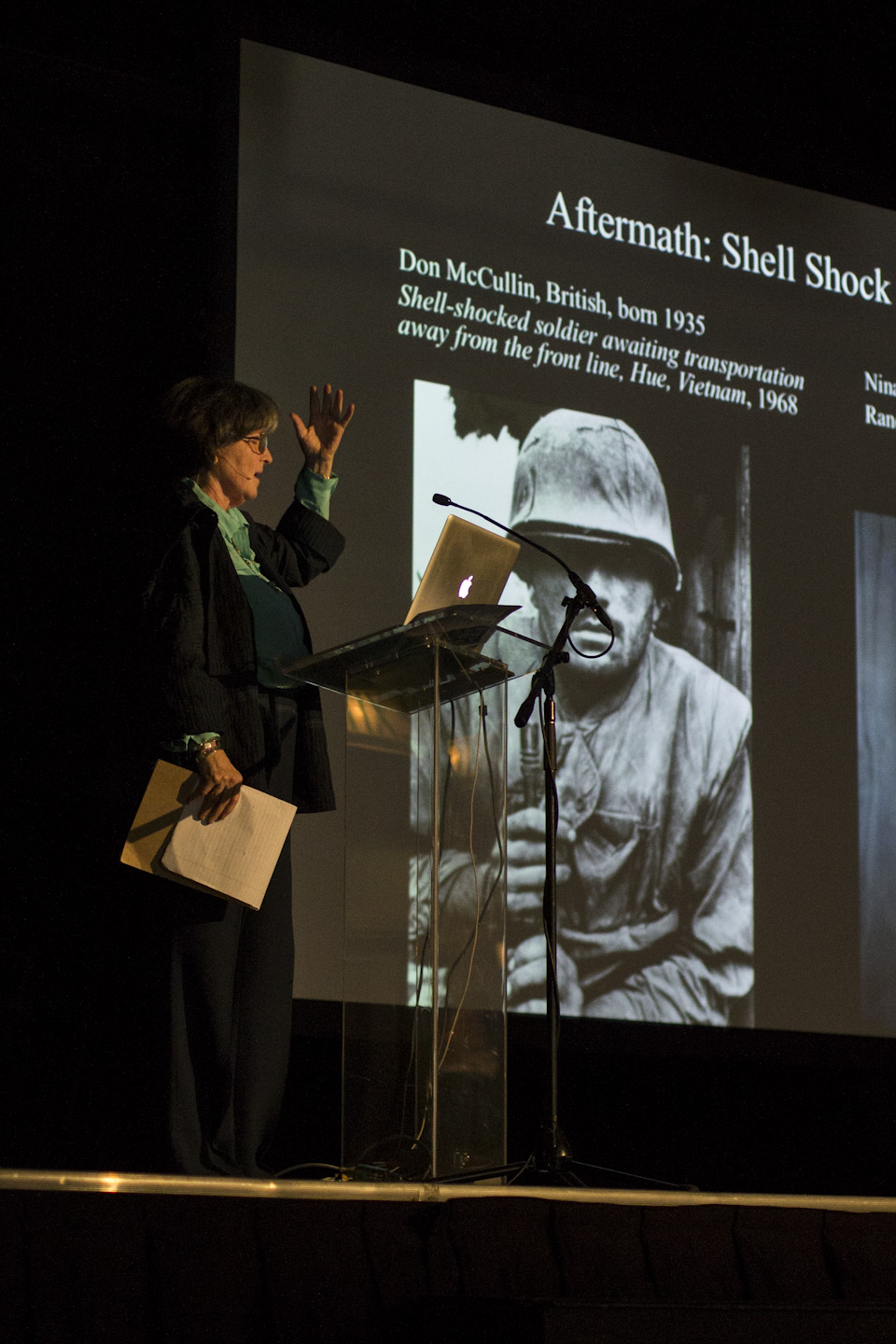

Violence in art is a hot topic if you spend time among Christians involved in the arts. After much rich discussion in the spring 2012 faith and film cinema and media arts integrated seminar, most of us seemed to be in agreement. Violence, when used without gratuity or indulgence, conveys ugly truth. Ugly truth is still truth. Therefore, we ought to portray violence where it best represents truth.

Ephesians 5:11-14 orders Christians: “Take no part in the unfruitful works of darkness, but instead expose them. For it is shameful even to speak of the things that they do in secret. But when anything is exposed by the light, it becomes visible, for anything that becomes visible is light.” Many Christians take the first two sentences without the context of the third. They speak so seldom of anything shameful that they never expose it with light.

“The Patriot” contains far more blood than “The Lord of the Rings,” yet it is not wrong to watch or be moved by this film. It exposes to light the horror of war and of our country’s history. You are supposed to watch the movie and squirm, and cry and walk out of the theater angry at the injustice in the world.

Of course, violence appears in many art forms, yet the discussion always comes back to film as it portrays the image of violence in an immediate, shocking way. However, let us not forget that the Bible is a deeply violent book. The children of Egypt die in the plagues, Sodom and Gomorrah are demolished and the Israelites engage in countless battles — yet our holy book is not immoral because it contains these truths to enlighten and to instruct.

Violence in art is not without danger. What the Bible does not do is glory in violence. It speaks in simple language; Exodus 11:9 reads, “At midnight the Lord struck down all the firstborn in the land of Egypt …” without detail. Movies like those in the “Saw” franchise are unedifying, revolting exaltations of violence.

Finally, even in films that use violence well, it is up to the individual to self-censor what he knows he cannot handle. If something raises in you a lust for violence, however innocuous it might seem to another, it is your job to avoid it.

The world is complicated. It is not as simple as: “Violence is bad.” Intent matters. Context matters. But we must not let the need for discretion trick us into thinking the world is not a violent place; sometimes the ugly truth in violent art can remind us to live for the kingdom of God as this world is fallen.