His drug use is explicit. His language is foul and his temper is explosive. Tension is

palpable as he brutally stabs a hitchhiker and leaves him for dead alongside the road. This is how we meet Sam Childers. But the life of this man does not unfold as an average crime-filled and depraved tale of woe. Childers not only finds God, but he begins a long and imperfect journey of missionary enterprise in the Republic of South Sudan during the second Sudanese civil war. What separates the story of Childers from any other heroic or mercenary legend is the fact that it really happened.

Main character changed by Christianity, mission trip

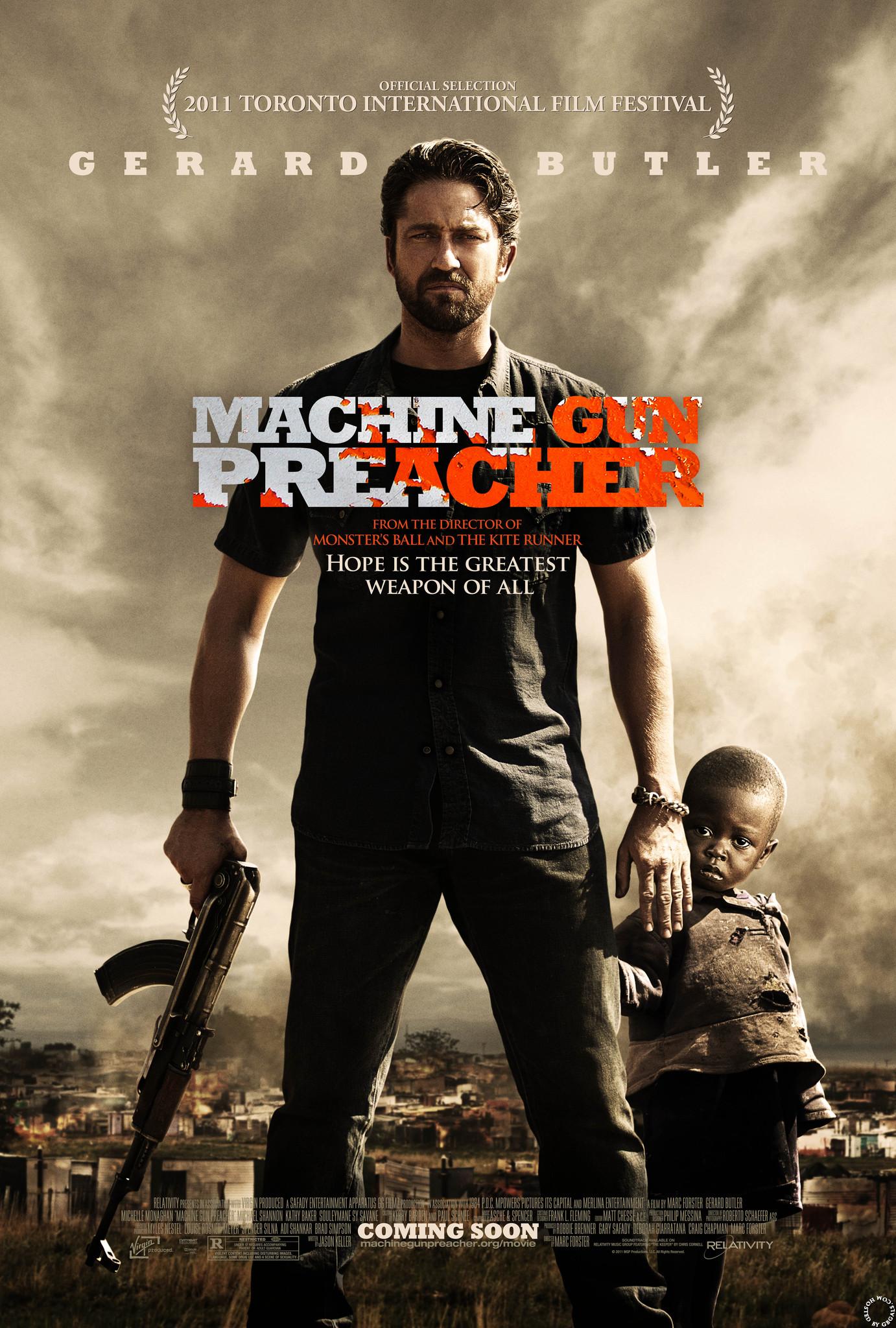

Childers, played by Gerard Butler, was born in Pennsylvania and cultivated a life of

violence in his youth that blossomed into drug dealing, armed robbery and incarceration as an adult. His depraved lifestyle is assaulted and called into question when his wife, Lynn, played by Michelle Monaghan, quits her job as a stripper after becoming a Christian and returns to the church of her youth. Apparently fed up with his life, Childers accompanies his wife to church. His conviction leads him to repentance and he is baptized the very same day.

The opportunity to join a group on a short-term mission trip to northern Uganda sets the

stage for the rest of his life and work in south Sudan. While on that trip, Childers ventures into south Sudan and witnesses the atrocities being committed by the Lord’s Resistance Army. His resolve to aid the most vulnerable children in the area compels him to not only establish a place of refuge for them, but take up arms and begin an offensive military assault against the LRA.

As Childers becomes more invested in his work in South Sudan, the line between the role

of missionary and mercenary becomes increasingly unclear. This is evident when, dressed in army green attire and combat boots, he leads his team of Sudanese People’s Liberation Army freedom fighters into offensive battles against the Lord’s Resistance Army with machine guns and rocket-propelled grenades. Childers’ marriage and family life become fragmented in the process as he sells his business and puts virtually his entire life up as collateral to fund his work in Sudan.

Graphic imagery displays human suffering

For the viewer, the actions of Childers are either justified or condemned in light of the

horrific atrocities he is fighting against. The audience is guided into the reality of human suffering through graphic imagery. The most expressive example is a scene in which Childers and his team come across a vehicle engulfed in flames alongside a rural village road in the middle of the night. After investigating the scene, they discover a large group of children hiding from the LRA in the bush.

Childers sets out to bring them all to his orphanage, but there is not enough room for them in the vehicle. He fills the truck with the sickest and youngest children and vows to return for the rest. Upon their return hours later, the children have vanished. All that is left is a pile of small charred corpses alongside the still-burning truck. He was too late.

Christian faith central to film’s story

As the title suggests, the filmmakers did not shy away from establishing Childers’ Christian faith as the foundation of his story. Moreover, Butler does a surprisingly credible job when he steps up to the pulpit of Childers’ Pennsylvania church. For the majority of the film, Childers attempts to maintain his balance as he straddles the roles of traditional American pastor and almost immortal “white preacher,” a title that he acquires among the children of South Sudan.

However, “Machine Gun Preacher” is nothing like the popular faith-based films released

in recent years. Childers spends a fair amount of time, as Christians often say, “in the flesh.”

His crisis of faith and questions of doubt are uncensored in ways that are almost unthinkable in traditional Christian films.

Films shows conflict, lacks historical context

Yet it is precisely for this reason that the film is able to resonate with such a broad audience. The film shows that “God don’t always call the good,” as Childers says. And while some might expect the film to end with some form of hopeful closure or reconciliation on Childers’ part, it doesn’t. Why? Because for the real Sam Childers, it hasn’t.

“Machine Gun Preacher” provides neither an ideal standard for ministry nor an ideal

missions ideology. The film does not completely untangle the complexities and contradictions of Sam Childers’ life and work; the truth is, it is nearly impossible to completely flesh out all the questions and struggles surrounding the film’s content in 127 minutes.

The film endeavors to illuminate more complexities in Childers’ character than it can handle. As the credits roll, the viewer is convinced that Childers is conflicted, but is unable to affirm much more than that. And while the film provides a basic understanding of the war in South Sudan, more detailed historical context would have enabled the viewer to better understand the plot’s relation to the very real and only recently resolved conflict in the country. Yet his fragmented testimony translates into an engaging and thought-provoking display on film.

Viewers be warned: This film is not for the faint of heart. Before the credits roll, you will be confronted, questioned and even offended. But for those who are up for the challenge, the zeal and resolve of Childers’ work is a living legend worthy of being known.

For more information on the work of Sam Childers or the film, visit

www.machinegunpreacher.org