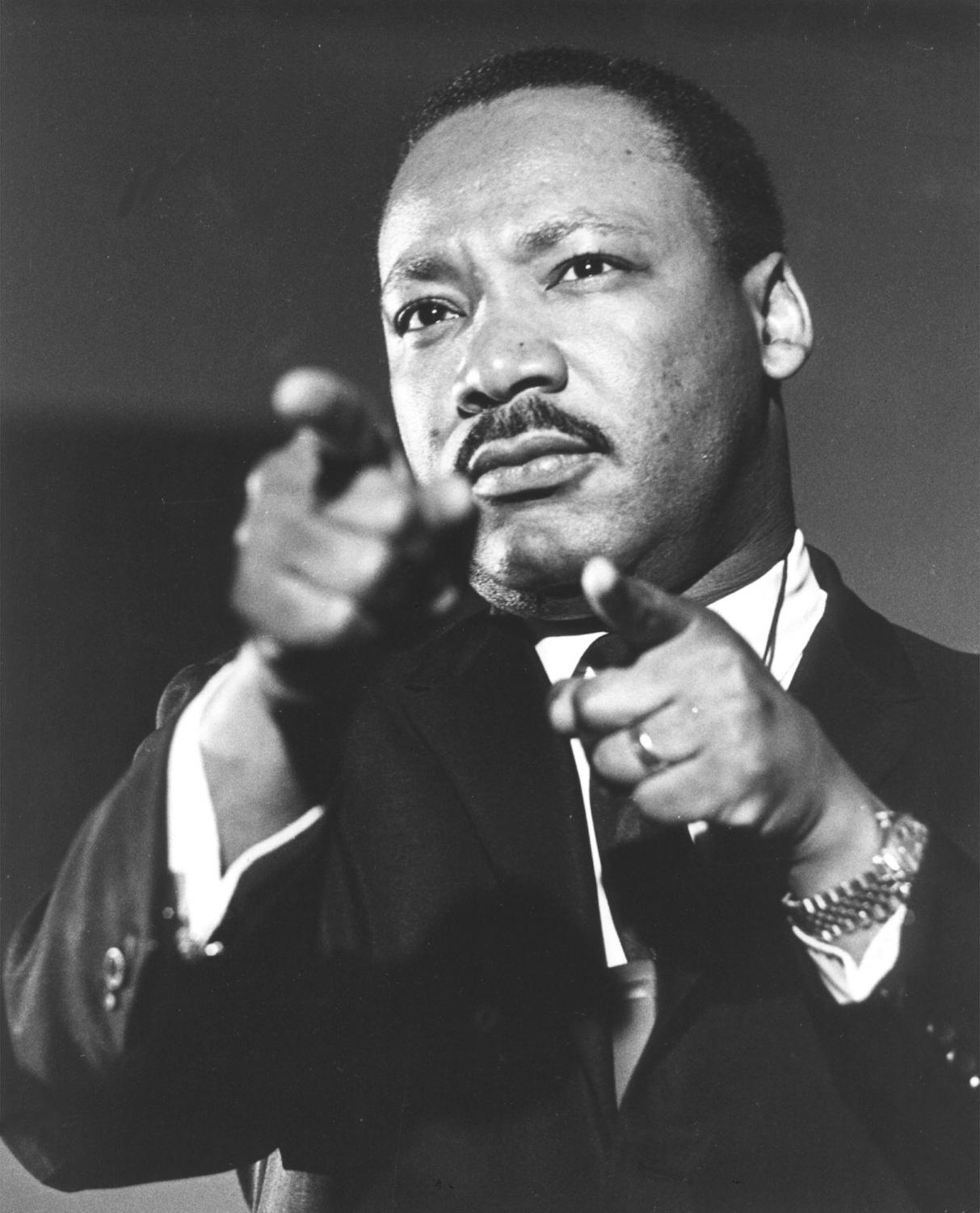

NEW YORK — Nearly 40 years after the assassination of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., some say his legacy is being frozen in a moment in time that ignores the full complexity of the man and his message.

”Everyone knows –even the smallest kid knows about Martin Luther King –can say his most famous moment was that ‘I have a dream’ speech,” said Henry Louis Taylor Jr., professor of urban and regional planning at the University of Buffalo. ”No one can go further than one sentence. All we know is that this guy had a dream. We don’t know what that dream was.”

King was working on anti-poverty and anti-war issues at the time of his death. He had spoken out against the Vietnam War and was in Memphis when he was killed in April 1968 in support of striking sanitation workers.

King had come a long way from the crowds who cheered him at the 1963 March on Washington, when he was introduced as ”the moral leader of our nation” –and when he pronounced ”I have a dream” on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial.

By taking on issues outside segregation, he had lost the support of many newspapers and magazines, and his relationship with the White House had suffered, said Harvard Sitkoff, a professor of history at the University of New Hampshire who has written a recently published book on King.

”He was considered by many to be a pariah,” Sitkoff said.

But he took on issues of poverty and militarism because he considered them vital ”to make equality something real and not just racial brotherhood but equality in fact,” Sitkoff said.

Scholarly study of King hasn’t translated into the popular perception of him and the civil rights movement, said Richard Greenwald, professor of history at Drew University.

”We’re living increasingly in a culture of top 10 lists, of celebrity biopics which simplify the past as entertainment or mythology,” he said. ”We lose a view on what real leadership is by compressing him down to one window.”

That does a disservice to both King and society, said Melissa Harris-Lacewell, professor of politics and African-American studies at Princeton University.

By freezing him at that point, by putting him on a pedestal of perfection that doesn’t acknowledge his complex views, ”it makes it impossible both for us to find new leaders and for us to aspire to leadership,” Harris-Lacewell said.

She believes it’s important for Americans in 2008 to remember how disliked King was before his death in April 1968.

”If we forget that, then it seems like the only people we can get behind must be popular,” Harris-Lacewell said. ”Following King meant following the unpopular road, not the popular one.”

In becoming an icon, King’s legacy has been used by people all over the political spectrum, said Glenn McNair, associate professor of history at Kenyon College.

He’s been part of the 2008 presidential race, in which Barack Obama could be the country’s first black president. Obama has invoked King, and Sen. John Kerry endorsed Obama by saying ”Martin Luther King said that the time is always right to do what is right.”

Not all the references have been received well. Sen. Hillary Rodham Clinton came under fire when she was quoted as saying King’s dream of racial equality was realized only when President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

King has ”slipped into the realm of symbol that people use and manipulate for their own purposes,” McNair said.

Harris-Lacewell said that is something people need to push back against.

”It’s not OK to slip into flat memory of who Dr. King was, it does no justice to us and makes him to easy to appropriate,” she said. ”Every time he gets appropriated, we have to come out and say that’s not OK. We do have the ability to speak back.”